The world's top

300 airlines in review

Find the world's safest and best value airlines plus 12,000 reviews and daily news updates.

The world's top 300 airlines in review

Find the world's safest and best value airlines supported by 12,000 reviews and daily news updates.

Featured articles

View moreNTSB Final Report: causes of the midair collision at Reagan National Airport

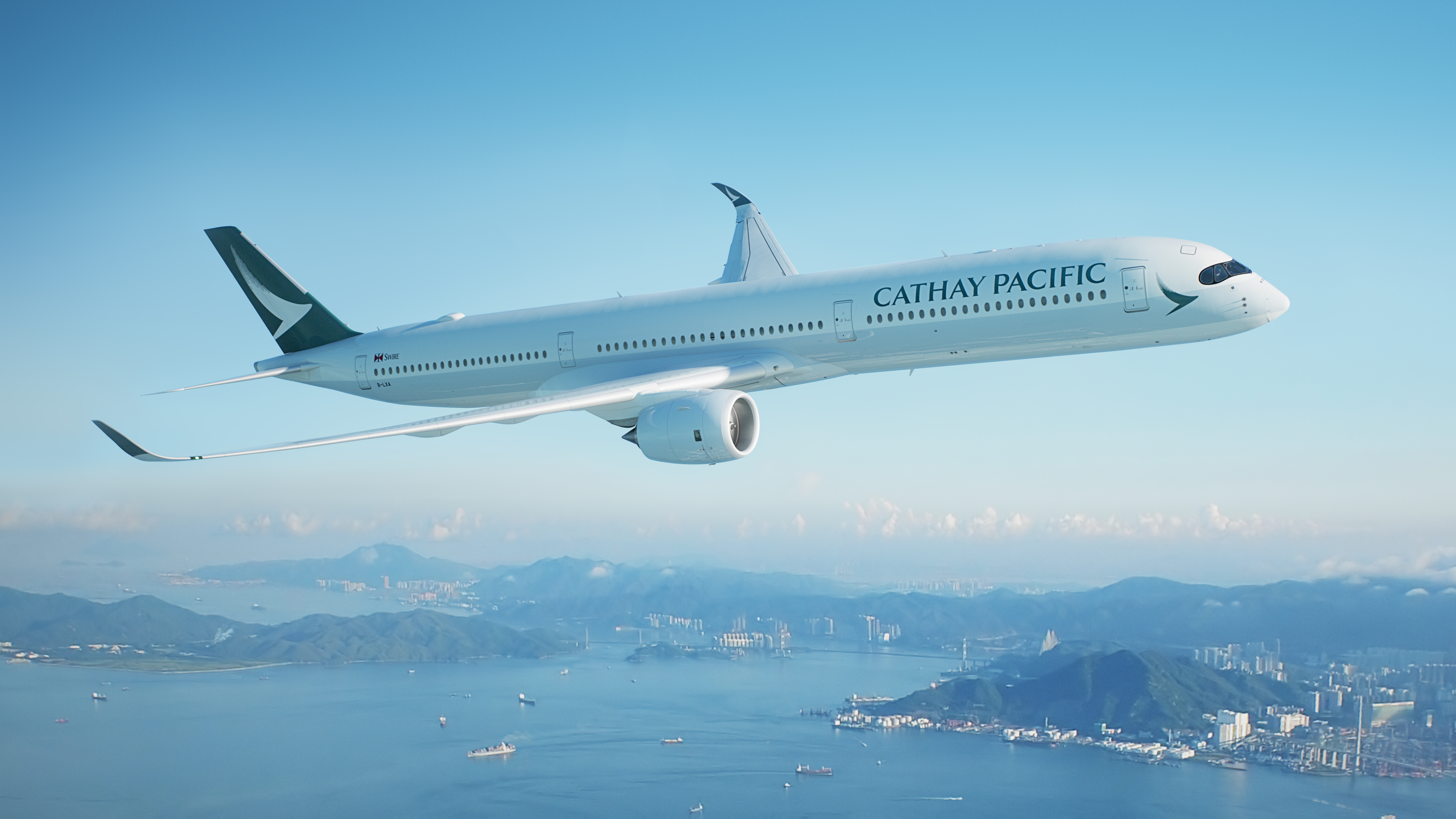

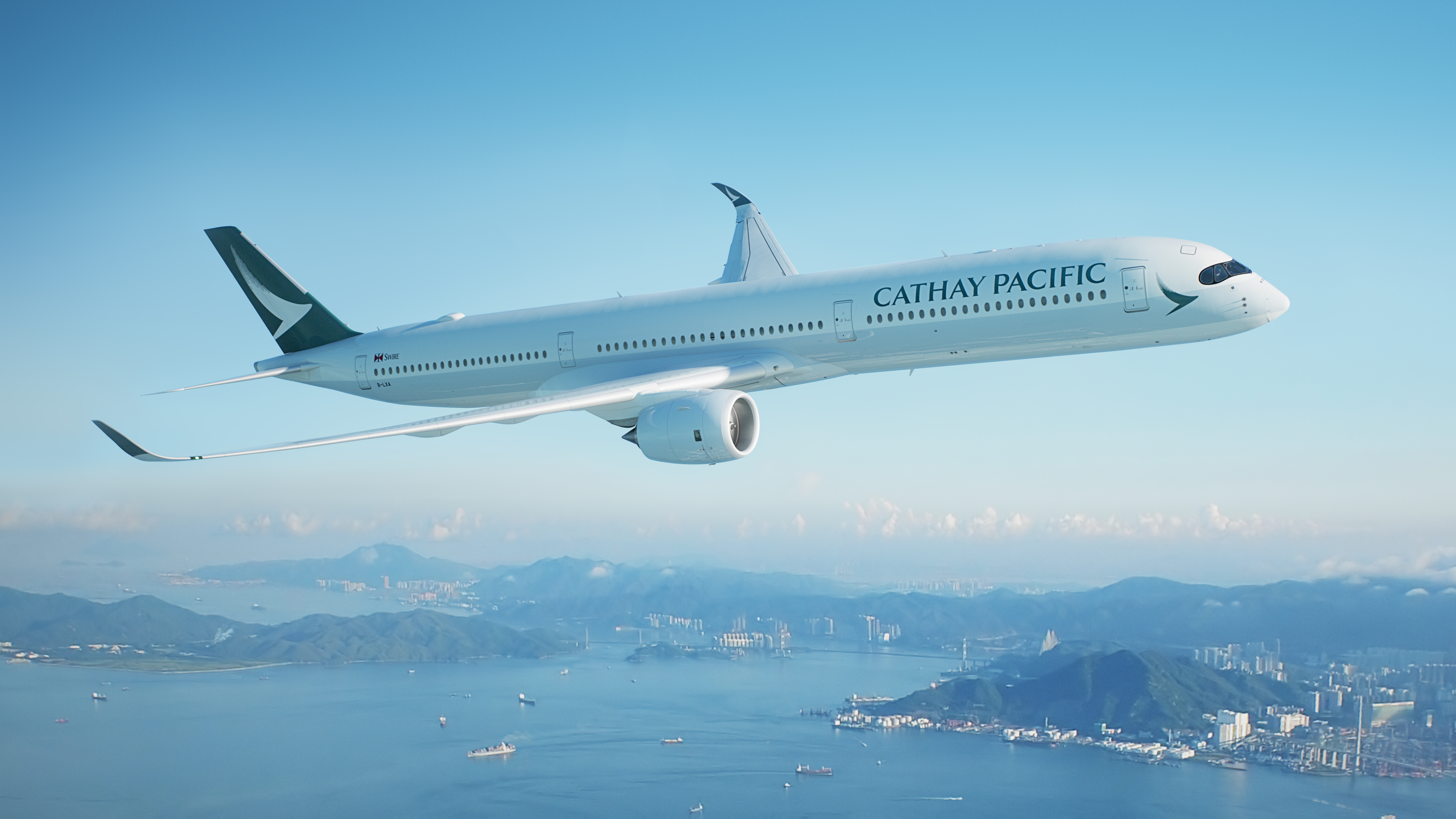

Cathay Pacific marks 80 years of aviation heritage – with Australia at the heart of its history

LATAM 777’s high-stakes rejected takeoff in São Paulo prompts an investigation

.jpg)

How Manston Airport could reopen-the legal approval, the delays, and the realistic timeline

AirAsia X low cost flights to London are back!

Latest news and reviews

View more

Vietjet Air wins Global Workplace Awards – what this means for passengers

The awards highlight more than culture — they signal operational stability in an industry where staff shortages often cause disruption.

Feb 27, 2026

Airline Ratings

Cathay Pacific marks 80 years of aviation heritage – with Australia at the heart of its history

From its 1946 Sydney-linked origins to today’s A350 and 777 fleet, Cathay Pacific’s 80-year story reflects a deep, enduring connection with Australia.

Feb 27, 2026

Airline Ratings

How Manston Airport could reopen-the legal approval, the delays, and the realistic timeline

Manston Airport is approved to reopen, but planes are unlikely to return soon. Airspace approval, funding, and construction still stand between the runway and real flights.

Feb 25, 2026

Josh Wood

NTSB Final Report: causes of the midair collision at Reagan National Airport

The NTSB final report found that the DCA midair collision between American Eagle Flight 5342 and a U.S. Army helicopter resulted from a separation breakdown, airspace design risks, and limits of visual separation.

Feb 19, 2026

Josh Wood

This Canadian airline flies 49-year-old aircraft: we tell you why

Air Inuit operates one of the world's oldest fleets, including the Boeing 737-200 Classic, and almost 50-year old Twin Otters. We tell you why, and how the airline uses these aircraft in Arctic conditions.

Feb 19, 2026

Josh Wood