Details of the struggle by the pilots of Lion Air Flight 610 to maintain control of the Boeing 737 MAX have again underscored the questions surrounding the accident ahead of the release this week of a preliminary report into the disaster.

They include why the plane continued to display faults that had been present on previous flights after the airline reportedly fixed them and whether the pilots attempted to follow a procedure that would have neutralized a new system that may have contributed to the crash.

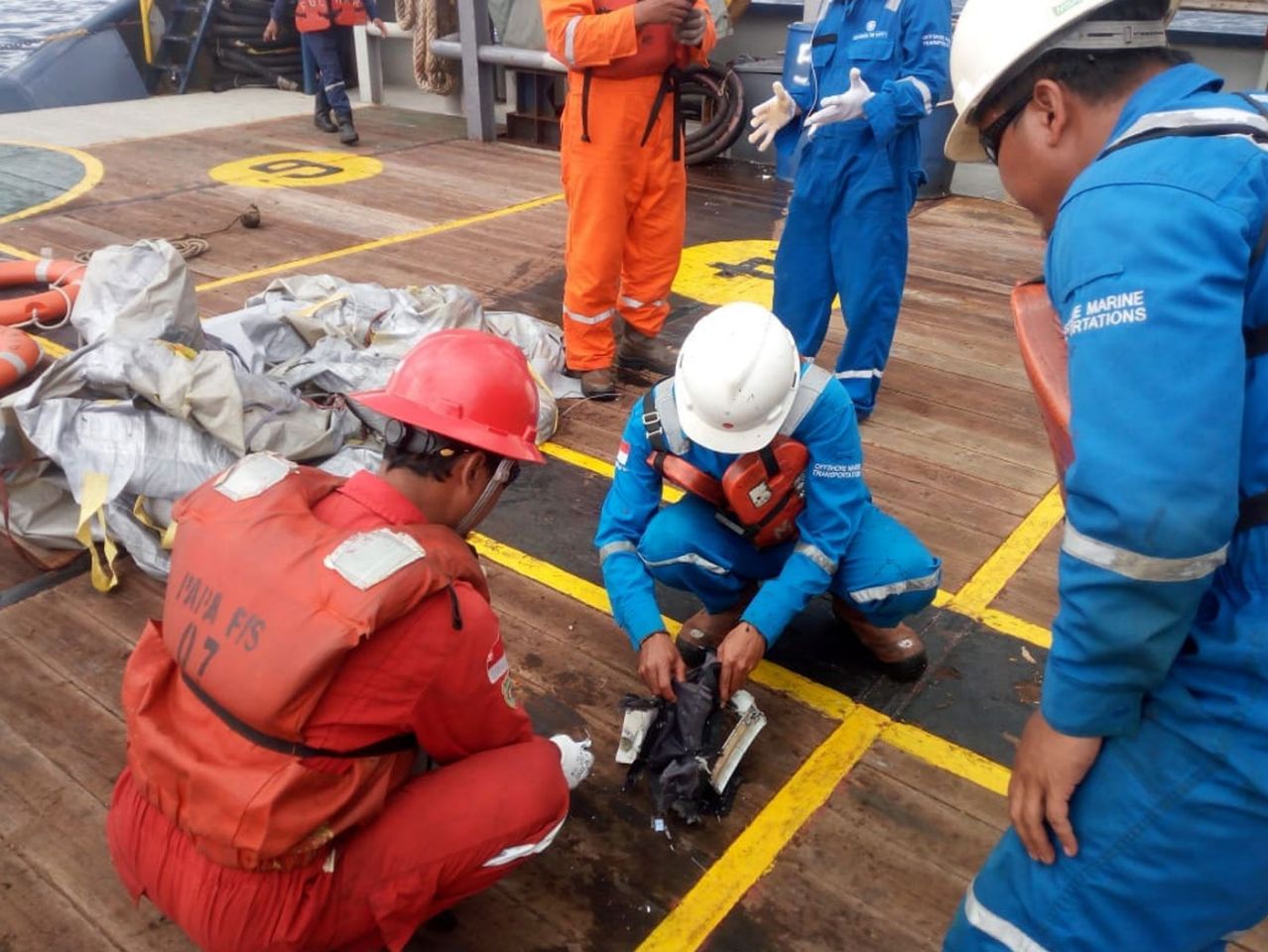

The Boeing 737 MAX 8 slammed into the sea on October 29 just 13 minutes after taking off from Jakarta, killing all 189 on board.

Investigators have already revealed that an angle of attack sensor was feeding bad data to the aircraft’s flight computers and causing a new safety system that helps prevent an aerodynamic stall, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), to push down the plane’s nose.

This resulted in a Boeing safety bulletin and a strongly-worded US Federal Aviation Administration emergency Airworthiness Directive warning pilots to follow existing procedures to turn off the autopilot and trim stabilizer if they found themselves in a situation similar to that experienced by Lion Air.

Reported comments by a senior safety official to the Indonesian Parliament last week indicated this did not happen in the Lion Air crash.

CNN Indonesia reported on November 22 that Indonesian National Transportation Safety Committee official Nurcahyo Utomo told the parliament that the plane experienced a stick shaker warning of an impending aerodynamic stall and this prompted the MCAS to push down the aircraft’s nose.

Nurcahyo said the pilots kept opposing the MCAS until “the end of flight”.

He said the pilots trimmed the plane when the system pushed the nose down but finally the number of trims by the pilots shrank, the load on the control yoke became heavier “and the plane dropped”.

The safety official pointed to the similar problems plaguing the plane on the previous night as it operated a flight from Bali to Jakarta.

He said pilot in that case had turned off the stabilizer trim to stop the MCAS from moving.

Bloomberg reported the pilots faced “a cacophony” of warnings and fought to pull the aircraft out of a dive in the plane’s final moments by applying as much as 100lbs of pressure to the control column.

The news service said the pilots repeatedly countered the plane’s attempt to lower the nose by trimming it in the opposite direction and pulling on the control yoke.

This saw it lose and gain moderate amounts of altitude until the final dive.

The FAA’s AD warned that an erroneous high single angle of attack sensor input received by the flight control system could lead to repeated nose-down trim commands of the horizontal stabilizer.

“This condition, if not addressed, could cause the flight crew to have difficulty controlling the airplane, and lead to excessive nose-down attitude, significant altitude loss, and possible impact with terrain,’’ it said.

The AD required flight crew to comply with the runaway stabilizer procedure in the Boeing operating procedures manual. This includes disengaging the autopilot, moving the stabilizer trim cutout switches to cutout and controlling the aircraft pitch attitude with the control column and main electric trim. It echoed a Boeing safety bulletin issued earlier.

Investigators are still searching for the cockpit voice recorder which is expected to further flesh out details of the pilots’ actions in the plane’s final moments.

Boeing has also come under fire from some US pilots who say it failed to provide flight crew and airlines with details about the MCAS system, a control law added to the plane’s flight control software to ensure the MAX feels the same to pilots as a older 737s when it enters and recovers from a stall.

The Allied Pilots Association criticised Boeing’s assertion that a safety bulletin issued after the crash was meant to reinforce procedures already in the 737 MAX flight manual.

“They (Boeing) didn’t provide us all the info we rely on when we fly an aircraft,” association spokesman Dennis Tajer told CNN. “The bulletin is not re-affirming, it’s enlightening and adding new info.”

However, Boeing’s chairman and chief executive Dennis Muilenburg vigorously defended the company, denying that the company hid details of the MCAS.

Muilenburg said the company’s service bulletin and the FAA’s AD pointed to existing procedures to handle inaccurate angle of attack data.

Also in the spotlight are Lion Air’s maintenance procedures.

The plane had suffered problems with speed and angle of attack readings, which measure the angle of the aircraft’s nose relative to the oncoming airflow, on previous flights.

READ: Lion Air had the same problems on four previous flights.

The airline said it had addressed the problem and replaced a faulty sensor after a flight from Bali to Jakarta sent the flight into a wild dive and made passengers sick.

Lion has accreditation under the respected International Air Transport Association Operational Safety Audit (IOSA) and has been removed, along with other Indonesian carriers, from the EU’s blacklist.

However, an investigation by The New York Times claimed that Lion Air was so obsessed with growth that it failed to build a proper safety culture.

Government safety investigators told the TImes the company’s political ties allowed it to circumvent their recommendations and to play down instances that would cause alarm elsewhere.

Former employees told the paper the airline became adept at passing malfunctioning equipment from plane to plane rather than fixing problems.

Lion Air has denied the company cut corners and said the company’s twin priorities were growth and safety.