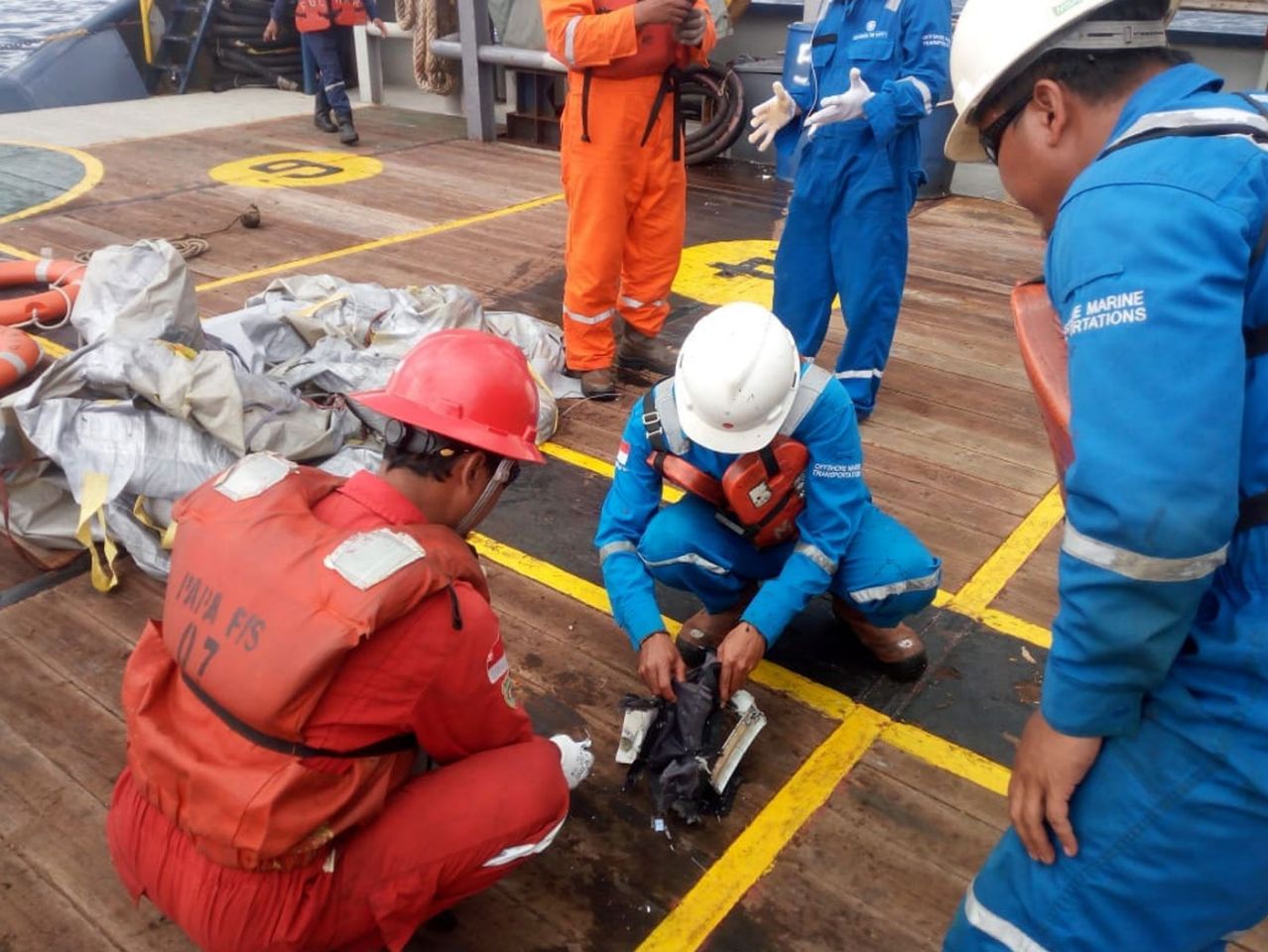

The final report by Indonesian crash investigators into the Lion Air Boeing 737 MAX tragedy has found design and certification shortcomings combined with airline maintenance issues and pilot errors to bring down the aircraft.

The report by Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee (KNKT) into the October 29, 2018 tragedy that killed 189 people found that a series of factors led to the tragedy, starting with Boeing’s design of new flight control software.

The flight control software, known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), was designed to make the MAX handle in the same way as its predecessors when a jet’s nose was pointing too high in an elevated angle of attack.

MCAS was an extension of the existing speed trim system and pushes down the nose of the aircraft when it detects a high angle of attack.

Faulty sensor readings on Flight JT610 caused MCAS to activate and continually and aggressively push down the aircraft’s nose push.

READ: MAX crisis sees Boeing oust head of commercial airplanes.

The crew of flight JT610 battled with MCAS after leaving Jakarta but failed to follow procedures that would have deactivated the automatic stabilizer trim system and ultimately lost control.

That procedure, which involved flicking two “stab trim” switches to cutout, was followed in similar circumstances on a flight the previous night and prevented a similar disaster.

The report found that during the design and certification of the Boeing 737 MAX assumptions were made about how pilots would respond to malfunctions “which, even though consistent with current industry guidelines, turned out to be incorrect”.

“Based on the incorrect assumptions about flight crew response and an incomplete review of associated multiple flight deck effects, MCAS’s reliance on a single sensor was deemed appropriate and met all certification requirements,’’ it said.

Among the problems identified by investigators was a decision by Boeing to classify hazards associated with an uncommanded MCAS activation on the MAX as “major” rather than “hazardous” or “catastrophic”.

Investigators also noted the lower classification meant Boeing did not test the full 2.5 degrees of stabilizer movement that could be commanded by MCAS at low speeds in a flight simulator or look at repetitive erroneous MCAS activations.

Boeing also followed US Federal Aviation Administration guidance that pilots would respond within three seconds to any changes in flight conditions but it took the Lion Air pilots longer.

“In the accident flight, the system malfunction led to a series of aircraft and flight crew interactions which the flight crew did not understand or know how to resolve,” the report said

“It is the flight crew response assumptions in the initial design process which, coupled with the repetitive MCAS activations, turned out to be incorrect and inconsistent with the FHA classification of Major.”

The KNKT said the fact MCAS was designed to rely on a single angle of attack sensor made it vulnerable to erroneous input from that sensor.

Investigators were also critical that Boeing did not tell pilots about MCAS or include more detailed use of trim in the flight manuals and in-flight crew training.

This made it more difficult for flight crews to properly respond to uncommanded MCAS, they said.

Also a problem was the fact that an alert telling pilots that the plane’s two angle-of-attack sensors were giving different readings was not working.

Although Boeing has said this was not essential to flying the plane, the report noted the lack of an angle-of-attack disagree alert meant a miscalibrated AOA sensor could not be documented by the flight crew and was therefore not available to help maintenance identify the miscalibrated AOA sensor.

The AOA sensor installed on the accident aircraft had been miscalibrated during an earlier repair by a US company. Investigators said this miscalibration was not detected during the repair.

The investigation could also not determine that the installation test of the AOA sensor was performed properly by an engineer.

The sensor was replaced in Denpasar after problems on previous flights and ahead of the flight before the fatal accident.

A lack of documentation on the flight previous to the accident flight and maintenance log meant that information was not available to the maintenance crew in Jakarta or the accident pilots “ making it more difficult for each to take the appropriate actions”.

The report also noted photographs provided by the engineer as evidence of a satisfactory installation test result were not of the accident aircraft and were discounted.

Another problem uncovered by investigators was a lack of effective management by the pilots of multiple alerts, repetitive MCAS activations, and distractions related to numerous ATC communications.

“This was caused by the difficulty of the situation and performance in manual handling, NNC (non-normal checklists) execution, and flight crew communication, leading to ineffective CRM (crew resource management) application and workload management,’’ the report said.

“These performances had previously been identified during training and reappeared during the accident flight.”

The report revealed the first officer’s performance in a 2013 simulator check had been deemed unsatisfactory due to what an assessor described as “a lack of situational awareness and judgment” and there had been problems in subsequent checks.

As recently as April 2017, an assessor had noted the first officer has shown problems with stall recovery “due to wrong concept of the basic principle for stall recovery in high or low level”.

The captain also had demonstrated a lack of appropriate technique during a stall on final approach assessment in 2015.

The Indonesian agency issued a number of safety recommendations calling on Boeing to consider the impact of flight deck alerts and indications on the flight crew, introduce changes to MCAS as well as modify procedures and training.

This included redesigning it to accommodate “a larger population of flight-rated pilots” and activating the AOA disagree alert.

It recommended that Lion Air establish a system to update company manuals after finding they were not updated in a timely manner and content had “several inconsistencies, incompleteness, and unsynchronized procedures”.

It also called on the airline to improve its hazard report managements so that it identified problems and provided proper mitigation.

Recommendations to the FAA included improved oversight of maintenance facilities and a closer look with other international regulatory authorities to review guidance about what information should be included in flight crew and engineers’ manuals.

It also said that , given the problems with the AoA disacgree alert, Boeing and the FAA should “ensure that certified and delivered airplanes have intended system functionality”.

Boeing said in a statement that it was addressing the KNKT’s recommendations and commended its work in the investigation.

“We are addressing the KNKT’s safety recommendations, and taking actions to enhance the safety of the 737 MAX to prevent the flight control conditions that occurred in this accident from ever happening again,” chief executive Dennis Muilenburg said.

“Safety is an enduring value for everyone at Boeing and the safety of the flying public, our customers, and the crews aboard our airplanes is always our top priority.

“We value our long-standing partnership with Lion Air and we look forward to continuing to work together in the future.”

Boeing has redesigned the way angle-of-attack sensors work with MCAS to include information from both sensors.

It will now activate only once in response to incorrect sensor information and will also be subject to a maximum limit that can be overridden with the control column.

“These software changes will prevent the flight control conditions that occurred in this accident from ever happening again,” the company said.

The FAA described the report as “a sober reminder” of the importance of ensuring safety is the first priortity.

“We welcome the recommendations from this report and will carefully consider these and all other recommendations as we continue our review of the proposed changes to the Boeing 737 MAX.” the agency said in a statement.

“The FAA is committed to ensuring that the lessons learned from the losses of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 will result in an even greater level of safety globally.

“The FAA continues to review Boeing’s proposed changes to the 737 MAX. As we have previously stated, the aircraft will return to service only after the FAA determines it is safe.”