MH370: Searchers correct the record

18 January, 2016

7 min read

By joining our newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Searchers for MH370 said yesterday that some recent media coverage of the multinational effort to find the Boeing 777 which disappeared on March 8, 2014 contained “significant inaccuracies and misunderstandings” which have been repeated by numerous outlets.

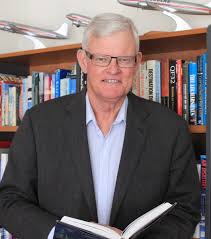

In a frank assessment the Australian Transport Safety Bureau took to task Captain Byron Bailey who has authored a report which has been quoted from by various media outlets.

It refutes suggestions by Captain Bailey that the ATSB rejects any possibility that MH370’s disappearance was the result of a person taking control of the aircraft.

“For the purposes of its search, the ATSB has not needed to determine – and has made no claims – about what might have caused the disappearance of the aircraft,” the statement said.

The ATSB added that “for search purposes, the relevant facts and analysis most closely match a scenario in which there was no pilot intervening in the latter stages of the flight.”

Mr Bailey also suggests that the ATSB has ignored information coming from sources that should be considered expert, such as Captain Simon Hardy a British Airways Boeing 777 captain.

Quite the contrary says the ATSB which has met with the British Airways captain and has been searching in and around the area identified by him.

AirlineRatings.com has covered Captain Hardy’s work as part of its coverage of the search for MH370.

Are serachers about to find MH370?

We have published the ATSB’s full statement here:

Inaccuracies in reporting on the search for MH370

18 January 2016

An article, The Case for Pilot Hijack by Byron Bailey, appearing in the 9-10 January 2016 edition of The Weekend Australian, contained significant inaccuracies and misunderstandings about the ATSB’s role in the search for MH370. Many of those inaccuracies were repeated in subsequent items both in The Australian and other media outlets. It is important that the ATSB corrects the record.

It is the responsibility of the Government of Malaysia, as the state of registration of the aircraft, to establish why MH370 disappeared and it has established an Annex 13 Investigation to undertake this activity. All enquiries in regard to the investigation should be directed to [email protected].

Australia was asked by Malaysia to assist in the search effort for missing flight MH370. The ATSB’s role is to lead the current underwater search operations for the missing aircraft. The ATSB continues to coordinate the Search Strategy Working Group and their collective work has led to the definition of the search area. This international team has expertise in satellite communications, aircraft systems, data modelling and accident investigation. It includes specialists from (and who draw on the broader expertise of) the following organisations:

Air Accidents Investigation Branch (UK)

Boeing (USA)

Defence Science and Technology Organisation (Australia)

Department of Civil Aviation (Malaysia)

Inmarsat (UK)

National Transportation Safety Board (USA)

Thales (UK)

Mr Bailey’s article claims that the ATSB rejects any possibility that MH370’s disappearance was the result of a person taking control of the aircraft. For the purposes of its search, the ATSB has not needed to determine – and has made no claims – about what might have caused the disappearance of the aircraft. For search purposes, the relevant facts and analysis most closely match a scenario in which there was no pilot intervening in the latter stages of the flight. We have never stated that hypoxia (or any other factor) was the cause of this circumstance.

Mr Bailey suggests that the ATSB has ignored information coming from sources that should be considered expert, such as Captain Simon Hardy. The ATSB carefully considers and assesses all credible work performed by external individuals and groups in relation to the MH370 search area, including that of Captain Hardy. The ATSB has been in telephone and email contact with Captain Hardy, and have met with him in our offices. Captain Hardy’s proposed location for the aircraft has been part of our search area since August 2014.

Mr Bailey’s article notes that the aircraft ‘avoided Thai military radar, then turned, after circling Zaharie’s home island of Penang.’ While the aircraft passed by Penang, the radar data shows that the aircraft certainly did not circle the island. The ATSB had to consider this issue, because the aircraft’s fuel consumption was an important issue in determining the search area.

Mr Bailey also asserts that “(a)nalysis of Malaysian military radar revealed the aircraft had climbed to 45,000ft as it tracked across northern Malaysia.”

The Malaysian military radar did record values from 5,000 to 50,000 ft. These were subsequently found to be inaccurate and so were disregarded by the search strategy team. The speed throughout that section of the flight was consistent with maintaining approximately FL 300 (or 30,000 ft). At the known weight of the aircraft, flight at 45,000ft would not have been possible at the aircraft speed reflected in the radar data.

Mr Bailey describes his experiences in a B777 simulator to put the ATSB’s assumptions about the end of the aircraft’s flight to the test. He states “The results revealed the ATSB’s theories are completely wrong. It claimed that most of the analysis from an estimated flame-out involved the aircraft making a left turn. But when we flamed out an engine at 37,000ft to simulate fuel starvation of the first engine, the autopilots remained on the commanded track.”

The ATSB’s report MH370 – Definition of Underwater Search Areas (published 26 June 2014 and updated 18 August 2014) states on page 33: “In the case of MH370 it is likely that one engine has flamed-out followed, within minutes, by the other engine.” On page 13 of the report, MH370 – Definition of Underwater Search Area Update, we state that: “The aircraft behaviour after the engine flame-out(s) was tested in the Boeing engineering simulator. In each test case, the aircraft began turning to the left and remained in a banked turn.” This is a reference to the behaviour of the aircraft after both engines had flamed out, which is an important question for the search.

Mr Bailey goes on to say: "Last month’s ATSB report had me deeply troubled. It bases search area calculations of projected flight paths on a grossly incorrect assumptions. A B777 cannot fly level at 37,000ft on one engine after a flame-out because of fuel starvation.”

The report in question actually agrees with Mr Bailey on this point. On page 11 of the report, we state:

“Based on the individual engine efficiencies the right engine would have flamed-out prior to the left engine. From this point the aircraft was operating on a single-engine and could not maintain any altitude above 29,000 feet.”

Mr Bailey also commented on the discovery of the flaperon on Reunion Island:

“When the flaperon was analysed by Boeing, the manufacturer said, along with US aviation safety consultant John Cox, that it had been broken off in a lowered position, consistent with the theory MH370 had made a controlled ditching into the sea. The ATSB initially said damage to the flaperon still supported the flame-out theory but showed the aircraft glided uncontrolled to a soft landing on the sea (hence no debris). Really?”

The ATSB has not made this statement. The analysis of the flaperon is the responsibility of the French judicial authorities who have it in their custody. No conclusion has yet been reached about the likely position of the flaperon immediately before it separated from the aircraft. To our knowledge, Boeing have not made any statements regarding the flaperon.

The ATSB has neither the authority under international agreements nor the need for the purposes of its search to make statements about why the aircraft disappeared. The successful completion of our search, based on sound analysis of confirmed data and using the best people, equipment and techniques, is still the best chance of arriving at an answer to the mystery of MH370’s disappearance.

Next Article

Virgin gets nod for Tiger deal

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

No spam, no hassle, no fuss, just airline news direct to you.

By joining our newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Find us on social media

Comments

No comments yet, be the first to write one.