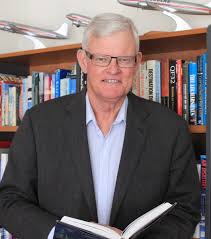

Captain John Leahy FRAeS, an expert in airline safety and pilot training with over 30,000 flying hours, offers a personal view of the Netflix documentary Downfall and highlights potential lessons from the Boeing 737 MAX tragedy.

We have reproduced John's views in full below. These reflect the position of this website and align with opinions held by many leading industry experts, including Greg Feith and John Goglia of the Flight Safety Detectives.

Initial Impressions of the Documentary

The release of the full-length Netflix documentary Downfall, covering the 737 MAX crashes, was highly anticipated by aviation professionals and concerned passengers alike. The central questions were:

Would it provide new information or deepen our understanding?

Would it remain objective and acknowledge that, while Boeing made serious errors, other factors also contributed to the twin tragedies?

Ultimately, the film mainly reiterated what many already knew—or thought they knew. I asked friends outside the aviation world who watched it what new insights they gained. The general consensus: “Nothing new—Boeing was to blame, and the program nailed it.” Another common sentiment was: “Those guys [pilots and passengers] never stood a chance.” The narrative that emerged was one of a poorly designed aircraft that even well-trained pilots couldn’t manage.

One moment the documentary highlights is that the Lion Air captain had “finished his training in the US,” which seemed intended to add credibility—perhaps even to drive home a fatal final nail. The scenes of grieving families, especially the captain’s wife declaring he was well-trained, are of course heart-rending. But they raise a question: do emotional scenes detract from a film that claims to pursue truth without drama?

The wife’s statement is, objectively, something she could not have known. He may have been diligent and done his best, but few pilots can perform beyond the limits of their training. As discussed later, pilot training quality is one of the major concerns in this tragedy.

SEE: Flight Safety Detectives dissect the Netflix Downfall documentary

Second Viewing: What Was Omitted?

I’ve now watched the documentary twice. On the second viewing, I looked for alternative narratives or critical omissions. The film largely stuck to verifiable facts—as expected with lawyers watching closely—but some significant omissions changed the narrative profoundly.

Let’s begin with key questions:

Key Omissions

1. Lion Air’s Regulatory History

Lion Air was banned from operating in Europe until 2017, per the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). This was not mentioned.

2. Massive Aircraft Orders Despite Safety Concerns

Lion Air, a relatively small Indonesian start-up by international standards, placed the second-largest order in aviation history in 2011: over 200 Boeing 737 MAX aircraft—while still banned in Europe. In 2013, they ordered a similarly large number of Airbus jets.

This raises questions:

Did the airline or the manufacturers conduct due diligence?

How did Lion Air leap from the aviation equivalent of the Fourth Division to the Premier League?

If Lion Air made a legitimate turnaround, what changes did they implement in culture, safety, and procedure? None were mentioned in the documentary.

Chain of Events Before the First Crash

The sequence leading to the October 2018 crash spanned over two weeks. During that period, the Lion Air maintenance division repeatedly dispatched the aircraft with faults in the airspeed system. A day before the crash, the Angle of Attack (AoA) sensor—a vital part—was replaced. Its origin remains debated, and it was clearly faulty. It should have failed post-installation tests, and the aircraft should have been grounded.

Why wasn’t Boeing consulted about this fault on a new aircraft? This is not discussed in the film. Instead, the aircraft flew again—leaving the pilots as the final line of defense.

Of course, pilots are trained to be exactly that. But only if they are thoroughly trained, prepared, and at the top of their game.

Lion Air ordered 201 Boeing 737 MAX 9 aircraft in 2012, making it the launch customer for that variant. — (Boeing)

The Day Before the Crash: An Omitted Flight

The documentary failed to mention a critical flight: the exact same aircraft flew the day before the crash—28 October 2018—with a different crew. That flight experienced an identical MCAS malfunction, and did not crash.

Here’s what happened:

The crew took off from Bali to Jakarta.

At liftoff, the stick shaker activated, falsely indicating a stall.

After flap retraction, MCAS kicked in and began aggressively trimming the nose down.

The crew, unaware of MCAS, diagnosed the issue and applied the Runaway Stabiliser Non-Normal Procedure: they flipped the STAB TRIM switches to CUT OFF, cutting electrical power to the stabiliser motor.

Control was restored, and the aircraft landed safely two hours later.

But this flight was not shown in the documentary.

Did you know this happened? Most viewers I spoke to did not, and some initially refused to believe it—until they checked reputable aviation sources and the official reports.

This event provides a rare direct comparison: two nearly identical flights, one day apart, with the same malfunction—one successful, one fatal.

Where is the investigation comparing these two flights? If it happened, it wasn’t made public. There is an immense opportunity to learn here.

The Jumpseat Pilot: The Unknown Hero

In the earlier, safe flight, there was a jumpseat pilot—from Lion Air’s full-service sister airline, Batik Air. According to Bloomberg:

“That extra pilot, seated in the cockpit jump seat, correctly diagnosed the problem and saved the plane.”

The next day, a different crew, unaware of that previous intervention, faced the same problem and crashed into the Java Sea. The flight data recorder confirms they were still consulting the Quick Reference Handbook in their final minutes.

The pilot in the jumpseat recognized the MCAS failure, told the crew to cut the trim motor, and the crew complied. That saved the aircraft.

Many passengers on that flight may not even know how close they came to dying.

This “unknown soldier” of aviation remains anonymous. Despite saving nearly 200 lives—comparable to Captain Sullenberger in the Miracle on the Hudson—he remains unacknowledged.

Twelve Full Minutes of Struggle

The documentary implies the Lion Air crash happened within minutes. That’s misleading.

Flight 610 was airborne for 12 minutes—from 23:20 to 23:32 GMT. At least 60% of that time was spent struggling with MCAS, as in the flight the day before.

This was a Memory Item drill—a known emergency procedure meant to be recalled instantly, no manual required.

The crew:

Did not perform the AIRSPEED UNRELIABLE checklist, despite clear indications and a stick shaker on liftoff.

Did not complete the RUNAWAY STABILISER procedure from memory.

Left full power on for the entire flight, leading to an impact beyond the aircraft’s maximum design speed.

In the final moments, the captain handed control to the inexperienced and reportedly 'below average' co-pilot—to look in the manual, for a Memory Drill.

Training and Skill Decline: A Global Threat

The emotional scenes of grieving families are powerful, but we must return to the documentary’s goal: seeking truth without emotion.

Can a trained pilot still be startled or overwhelmed after several minutes? In my 40+ years in training—at both legacy and low-cost carriers—I would argue: not if they’re trained properly.

In 2021, we wrote in Aerospace Magazine and AirlineRatings.com about Skill Decline and Skill Deficit: the gradual erosion of manual flying skills as automation increases and training gets cut.

After the Ethiopian crash in 2019, it became clear that:

Some regions lacked adequate pilot training, especially regarding the stabiliser.

Even US carriers had begun trimming essential training.

No wonder US ALPA union pilots later said: “This was beyond our training.” That’s accurate—but it should never have been true.

Generations of 707 and 737 pilots were trained rigorously on stabiliser failures. Around 2005, this stopped being emphasized. Full-flight simulator sessions barely touched on it.

MCAS Training: Too Little, Too Late

The documentary rightly criticizes Boeing for not including MCAS in the manuals or training. But:

On the 737-800 NG, Runaway Stabiliser training had already been minimized or dropped.

Even today, pilots don't need a dedicated MAX simulator to learn MCAS recovery—it looks and is handled identically to other trim runaways.

So while MCAS should’ve been documented, it did not require in-depth system knowledge. It was a Memory Item—meant to be applied instantly, from memory.

Have We Really Solved the Root Problem?

The documentary concludes with a comforting message: Boeing has changed, the FAA is reformed, and MCAS is fixed. We can fly the MAX again with confidence.

But have we addressed pilot training?

If training quality was a root cause—and it appears to be—then simply fixing MCAS is like putting a band-aid over a deep wound.

Today, MAX pilots receive targeted training on stabiliser systems. But this was always supposed to be part of the 737 curriculum. The “remedial” training is simply the proper training that had once been standard.

Old-School Flying in a Modern Age

The 737 remains a brilliant aircraft—perhaps one of the finest ever built. But you cannot cut corners on pilot training, especially for an aircraft that—underneath modern automation—is still a manual-flying workhorse.

Can a 737 still be flown upside down if needed? Absolutely. It lacks the Fly-By-Wire (FBW) protections found on newer designs like the A320. That’s not bad—it just means pilots must know what they’re doing.

Are new customers told this? Does Boeing mention that the 737 is not a direct counterpart to FBW aircraft like the A320?

Automation vs Training: The Final Question

Can automation solve these problems?

The industry is increasingly discussing eMCOs (Extended Minimum Crew Operations)—removing one pilot.

Yet even with two pilots, handling complex emergencies can be a struggle. On Qantas Flight 32 (A380, Singapore), it took all four pilots to save the aircraft.

So what happens with only one pilot?

Final Thoughts

This review does not aim to take sides. It raises questions that demand answers.

Two 737 MAX crashes should never have happened.

The 737 remains a superb aircraft. But it’s one that demands proper training.

You cannot automate your way out of inadequate training. And if we keep ignoring this lesson, the next failure may come from a completely different system—but with the same tragic result.

Have questions or want to share your thoughts?