The search for MH370, which disappeared over two years ago, must continue if Malaysia does not want to be accused of a cover-up by relatives and loved ones of those aboard.

MH370, a Boeing 777-200 with 239 passengers and crew disappeared on a routine overnight flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on March 14, 2014.

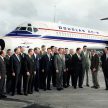

This week ministers from Malaysia, China and Australia meet to discuss the future of the search as the international team closes on completing the agreed 120,000 sq km.

Malaysia has come in for significant criticism for its handling of the initial stages of the search for MH370 with numerous officials giving conflicting information which gave the impression of confusion and cover-up.

Giving up now will only add to the doubts about the country’s commitment to finding MH370 particularly in view of the five pieces of debris that have been found over the past year.

The first was a flaperon discovered on Reunion Island in July last year, then two pieces from the horizontal tail turned up in Mozambique, next an engine cowl piece in South Africa and finally an interior panel on Rodrigues Island.

All these discoveries are consistent with ocean current modelling done in June 2014 that supports that the international search team is looking in the correct area 1800km west south west of Perth Australia.

The exact costs of the search are unclear but a report in the Telegraph put the cost at: A$190 million split three ways; Malaysia A$100 million; Australia A$70 million and China A$20 million.

China must bear more of the cost as the flight was also a code-share with China Southern Airlines and carried the airline’s flight number CZ748. There were 153 Chinese aboard the ill-fated aircraft.

When an airline code-shares (places its flight number and sells tickets on another airline’s aircraft) it must bear full responsibility for all aspects of the flight.

Last week the Australian Transport Safety Bureau said in its weekly update that over 110,000 sq kms had now been searched. It said bad weather had severely affected operations and delayed the search up to two months and also warned further delays could see it continue “well beyond the winter months”.

Three ships — the Fugro Discovery, the Fugro Equatoris and the Dong Hai Jiu 101 — are still engaged in the search.

History shows that we never give up trying to find ships or planes that disappear – particularly those that are high profile. RMS Titanic, the battleship Bismarck, battlecruiser HMS Hood and the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney are classic examples and there are many more.

Recently Microsoft co-founder Paul G Allen funded an eight year search which found the Musashi, one of the two largest and most technologically advanced battleships in naval history – 71 years after it was destroyed by American aircraft at the Battle of Lyete Gulf.

Searchers also continue – off and on – to look for Amelia Earhart who vanished in July 1937 while attempting the circumnavigation of the world. The disappearance of MH370 is unprecedented in modern history. Certainly aircraft have disappeared without a trace but not a modern commercial airliner with hundreds aboard.

The search is the most complex and scientific ever undertaken – and it’s multinational. The ATSB coordinates the Search Strategy Working Group and its collective work has led to the definition of the current search area.

This multinational team has extensive expertise in satellite communications, aircraft systems, data modelling and accident investigation. It includes specialists from: the UK’s Air Accidents Investigation Branch; Boeing; Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Organisation; Malaysia’s Department of Civil Aviation; Inmarsat; the US National Transportation Safety Board and Thales in the UK.

Malaysia and China must continue to fund the search and keep the international team led by the ATSB intact so that the vast amount of knowledge gained thus far is not lost.