Concorde was a masterpiece of engineering, a technological marvel and the greatest financial disaster in aviation history but for all who look skyward and dream, she is sadly missed.

Fifty-three years ago on March 2, 1969, Concorde 001 made its first test flight from Toulouse piloted by André Turcat. The first UK-built Concorde flew from Filton to RAF Fairford on 9 April 1969, piloted by Brian Trubshaw.

And just over eighteen years ago, on October 24, 2003, the Concorde, on most people’s bucket list, made her last flight, as age and economic reality finally caught up with her.

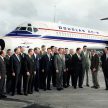

SEE stunning new colorized images of Douglas Pan Am propliners

She was the transport of choice for the rich and famous, the Concorde was part of a world beyond the reach of most people.

Celebrities who forked out the $20,000 for the return trip from London to New York have included Elton John, Sting, Mick Jagger, Joan Collins, Luciano Pavarotti, Sean Connery, Robert Redford, Elizabeth Taylor, Joan Collins, Mike Tyson, Annie Lennox, and Rod Stewart.

In 1985, Phil Collins used Concorde to perform at the 16-hour Live Aid both in London and Philadelphia before the show finished.

The plane was a favorite with the Queen and the late Queen Mother was reported to have taken the controls of one Concorde during a test flight.

In the final analysis, behind the glitz and glamour, the Concorde was one project that should never have gotten off the ground.

It was a product of the age of “speed and sputnik“, when it seemed there were no limits to what could be achieved in the skies.

The Concorde had its commercial genesis at the Paris Air Show in 1961, when French aircraft manufacturer Sud Dassault proudly displayed a model of the Super Caravelle, which could carry 70 passengers at supersonic speed.

It sped up British efforts to produce a supersonic jet, which had started in 1956.

By March 1962, the French and British governments intervened to merge the efforts in a joint Supersonic Transport project.

But the agreement reached in November 1962 contained no provision for a ceiling on the costs, estimated to be $414 million, nor was any review or cancellation process agreed on.

And there were already serious voices of caution.

Pan Am’s long-time adviser, Charles Lindbergh, warned of the environmental and economic problems the aircraft would face – well before they became major industry concerns.

At different times, both France and Britain wanted to abandon the project but because of the wording of the treaty, the other would seize the opportunity to recoup its own expenditure and, of course, maintain that it wanted the Concorde to carry on.

The aircraft in its original form was designed to carry up to 150 passengers 7696km at Mach 2.2 – just over twice the speed of sound.

But it was discovered that the plane would fall short of New York by almost 700km, so the aircraft was redesigned.

As work progressed, the very fine margins of the original concept became all too clear. Eventually, Concorde’s payload (passengers and baggage) performance settled at about 100 passengers between London and New York.

The first Concorde to fly took off in March 1969 when options had been received for 80 Concordes from 18 airlines, including Qantas.

In the same year, British Aircraft Corporation was predicting, on the most pessimistic assumptions, sales of 225 Concordes by 1975, though this was well down on the original estimate of 500.

However, industry expert and historian the late Reg Davies claimed very little research was ever done into the market for SSTs. According to Davies, British Aircraft Corporation produced a brochure in 1970 claiming that more than 30 percent of the market would pay first-class fares to travel on Concorde.

He notes the reality at the time was that only 7 percent of the market was first class and it was declining. Today, it’s less than 2 percent, with many airlines dropping first class over the North Atlantic. And development costs soared higher than the aircraft.

According to one estimate from the London-based Independent newspaper, the total write-off for the British and French governments was $34 billion, which works out to a taxpayer subsidy of a staggering $8000 for every passenger who has flown on Concorde.

By early 1973, most of the airlines had canceled their options as fuel prices took off and noise problems became a major issue.

Only government-owned Air France and BOAC put Concorde into service at no capital cost, after complex write-off and profit-share/loss underwriting arrangements were struck.

The first commercial flight was not until January 21, 1976, when a British Airways jet flew from Heathrow to Bahrain, at the same time as an Air France jet flew to Rio de Janeiro.

In 1984, British Airways, preparing for privatization, struck a $40 million deal with the government. It took all the Concorde spares and one grounded model and the profit/loss agreement was scrapped.

British Airways’ Concordes were on its books at zero value ever since privatization, which was essential for the aircraft to turn a profit.

The Russians were also focused on supersonic travel – not to take the rich and famous across the Atlantic, but to save time for scientists and military staff.

Government agencies believed that a fleet of 75 such aircraft was needed to cross the country and the Tupolev design bureau was given the task in July 1963. The problem of the sonic boom was dismissed as being just like thunder – and possibly not nearly as bad as the wrath that would follow any complaints to the authorities.

With its similar mission, it was inevitable that the Russian aircraft would be somewhat similar to the Concorde, though the arrest of Aeroflot’s (the Russian national airline) Paris manager at a cafe carrying a briefcase of Concorde plans gave rise to the “Concordski” label.

In fact, the Russian TU-144 was bigger, faster, more powerful and, many say, more advanced than the Concorde. Major differences between the two designs were the broad use of complex but lightweight titanium in the TU-144’s hottest structures and the use of turbofan engines with afterburners.

The first aircraft flew on December 31, 1968, but production models that appeared in 1972 were completely redesigned to address performance shortfalls. The aircraft was six meters longer, had a new wing, and could carry a much greater fuel load.

Tragically, the second production aircraft crashed at the Paris Air Show in 1973, apparently, after a cameraman standing in the cockpit fell on the controls when the pilot put the aircraft into a sharp turn to avoid another jet.

The TU-144 also suffered from excessive vibration and fuel-burn and ultra-high cabin noise. Despite these problems and the air-show crash, the TU-144 went into service carrying cargo in 1975, followed by passenger flights in 1977.

But passengers hated the cramped five-across cabin (Concorde is four across) and the vibration and noise did not help. After just 102 flights, the service of the TU-144 was terminated when a new, longer-range model, the TU-144D, crashed on a test flight, culminating in the grounding of the fleet, with some scrapped and others stored.

In 1994, a requirement by Boeing, McDonnell Douglas and NASA for research into high-speed transport saw one TU-144 restored to flying condition.

This was one of many attempts by the United States to build an SST with the first efforts dating back to 1958.

After years of informal work, Boeing established a supersonic project office in January 1958. But because of the enormous cost of the project, it was thought to be beyond the financial capability of any private company.

Despite doubts and because Pan Am’s order for six Concordes in 1963 forced the issue, President John F. Kennedy launched the US counter to the Concorde.

The US Federal Aviation Authority called for tenders from the US industry to build an aircraft superior to the Concorde. In December 1966, the US Government selected Boeing’s swing-wing 2707-200. Boeing was to build two prototypes over four years at a cost of $2.08 billion at a 1967 value.

Twenty-six airlines, including Qantas, took 122 delivery positions, with Pan Am, TWA, and Alitalia to be the first to take delivery.

But as work progressed, it became evident that the swing-wing design was flawed and might not even be able to carry any payload, while the level of noise it produced, together with the sonic boom, loomed as insurmountable difficulties.

Boeing scrapped the swing-wing in October 1968 in favor of a fixed delta-wing design. But as construction proceeded with the mock-up, the aircraft ran into another obstacle much greater than the sound barrier – cost.

Finally, the union of the environmental lobby and the critics of government spending won the day. In 1971, the US Senate and the House of Representatives voted to kill the project.

At the time, the US investment in 2707 was $1.47 billion and all the US had to show for it was a mountain of paperwork and a mock-up.

Despite the host of problems associated with supersonic travel, serious studies continued as aircraft manufacturers searched for answers on how to break the environmental and economic barriers.

In the mid-1990s, Boeing teamed with McDonnell Douglas, Pratt & Whitney and General Electric in a $1.8 billion NASA-funded study into a High-Speed Civil Transport. The study aircraft would carry 290 passengers at Mach 2.4 (2535kmh) and be able to fly from Los Angeles to Tokyo in just over four hours.

By 1996, Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and NASA defined a new baseline design for the HSCT program, the Technology Concept Airplane.

The TCA was intended to be profitable at fares only marginally higher than tickets on jumbo jets and to go into service in 2015. But the challenge of designing an aircraft that would carry three times the payload of the Concorde twice the distance, without increasing standard ticket prices, proved impossible and the project was scrapped. With it the promise of supersonic travel for the time.

But with new technological breakthroughs in engines and materials, the dream has been rekindled with Boom and others gaining momentum with more modest supersonic business jet style concepts.