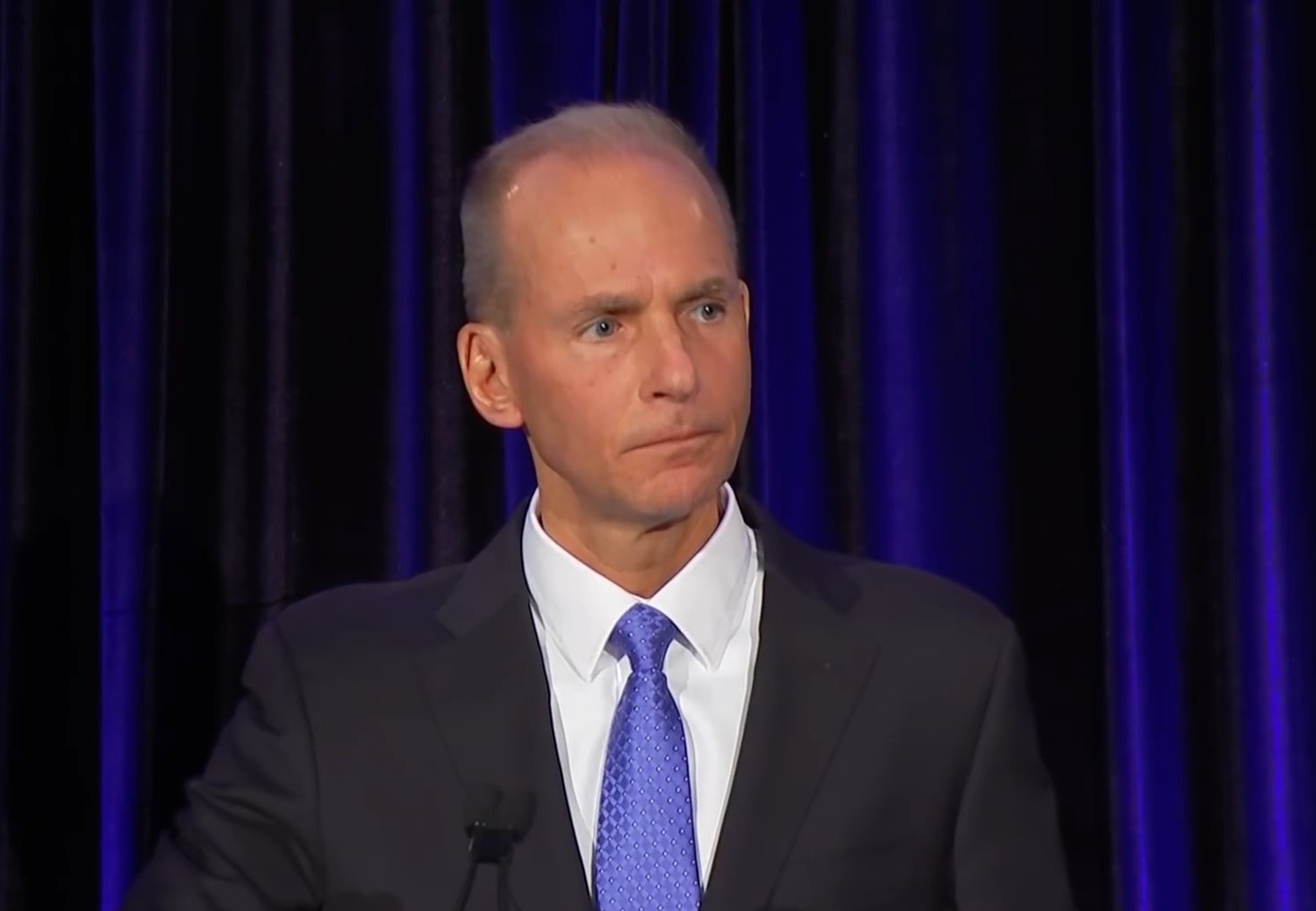

Boeing has removed chief executive Dennis Muilenburg as chairman in a move it says will allow him to concentrate on steering the company through the Boeing 737 MAX fiasco.

The announcement came on the same day a high-powered review of the 737 MAX certification process found faults at both the FAA and Boeing.

The global MAX fleet remains grounded after two tragedies involving the deaths of 346 people raised questions about flight control software and the way the new plane was certified.

It is not clear when it will return to service but US carriers, including United and American, have been canceling MAX flights until January.

Independent lead director David Calhoun will now chair Boeing’s board in a move the company said would allow Muilenburg to focus full-time on running the company as it worked to return the MAX to service, support customers and implement changes to sharpen the focus on product and safety services.

“The board has full confidence in Dennis as CEO and believes this division of labor will enable maximum focus on running the business with the board playing an active oversight role,’’ Calhoun said in a statement.

READ: European probe to delay Boeing deal with Embraer.

The board also plans in the near term to name a new director with deep safety experience and expertise to serve on the board and its newly established Aerospace Safety Committee.”

Muilenburg said in the same statement he was “fully supportive of the board’s action”.

“The board also plans in the near term to name a new director with deep safety experience and expertise to serve on the board and its newly established Aerospace Safety Committee,” he said.

The announcement did not mention the critical findings by the Joint Authorities Technical Review delivered earlier in the day.

The review was headed by former US National Transportation Safety Board head Chris Hart and included representatives from NASA and other regulators, including those from Europe, Australia, Canada, Japan and China.

It criticized both parties for the way they assessed and certified flight control software known as MCAS implicated in both MAX tragedies.

It was critical of the Boeing design process, the way changes were communicated as well as of the FAA’s oversight and staffing levels.

It also raised broader issues of increased cockpit automation and whether the certification needs to be modernized to take into account increasingly complex aircraft systems.

“As aircraft systems become more complex, ensuring that the certification process adequately addresses potential operational and safety ramifications for the entire aircraft that may be caused by the failure or inappropriate operation of any system on the aircraft becomes not only far more important but also far more difficult,’’ Hart said in a covering letter to the report.

The review called for rules applying to product changes should be revised to require a top-down approach where every change was evaluated from a whole aircraft system perspective.

“The JATR team determined that the Changed Product Rule process was followed and that the process was effective for addressing discrete changes,” it said

“However, the team determined that the process did not adequately address cumulative effects, system integration, and human factors issues.

It found some regulations were out of date and this meant some processes that addressed safety issues related to system integration and human factors were not applied to the MAX “or were only partially applied in a way that failed to achieve the full safety benefit”.

In looking at whether MCAS complied with system design and safety requirements and standards, the team was critical of certification documents submitted to the FAA.

“The lack of a top-down development and evaluation of the system function and its safety analyses, combined with extensive and fragmented documentation, made it difficult to assess whether compliance was fully demonstrated,’’ it said.

“The MCAS design was based on data, architecture, and assumptions that were reused from a previous aircraft configuration without sufficient detailed aircraft-level evaluation of the appropriateness of such reuse, and without additional safety margins and features to address conditions, omissions, or errors not foreseen in the analyses.”

It recommended that aircraft be assessed in a holistic manner with a system safety function independent from the design organization.

Other questions included the impact of the new design on operations and training and assumptions made by Boeing about how crews would react to MCAS as well as its decision not to tell pilots about the changes.

It found a decision to remove information about MCAS from Flight Crew Operations manual meant the FAA Flight Standardization board was not fully aware of the function and not in a position to adequately assess training needs.

It noted one of the assumptions used in Boeing’s functional hazard assessment for the 737 MAX —that a pilot would take immediate action to reduce or eliminate high control forces — was not consistent with the actions of the pilots in the two accidents.

It recommended that the FAA require a documented process to determine what information should be included in manuals as well as a review of training to ensure pilots are competent in handling trim problems.

Describing the review as “unvarnished and independent”, new FAA boss Steve Dickson said he was reviewing every recommendation and would ”take appropriate action”.

“Today’s unprecedented U.S. safety record was built on the willingness of aviation professionals to embrace hard lessons and to seek continuous improvement,’’ he said.

“ We welcome this scrutiny and are confident that our openness to these efforts will further bolster aviation safety worldwide.

“The accidents in Indonesia and Ethiopia are a somber reminder that the FAA and our international regulatory partners must strive to constantly strengthen aviation safety.”