Captain John Leahy FRAeS, an expert* in airline safety and pilot training with over 30,000 flying hours, offers a personal view of the Netflix documentary ‘Downfall’ and highlights potential lessons from the Boeing 737 MAX tragedy.

We have reproduced John’s views in full as under, and they are the views of this website and many other leading industry experts such as Greg Feith and John Goglia of the Flight Safety Detectives.

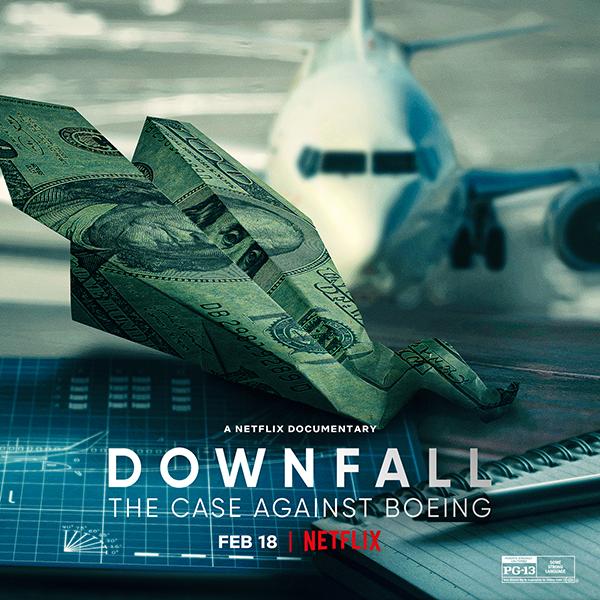

The release of a Netflix full-length documentary “Downfall” about the 737 MAX crashes was eagerly awaited by those of us that follow these matters carefully. It was also watched by many passengers, for obvious reasons. Would it bring any fresh knowledge or possibly unravel further what was already known? Would it be objective and embrace views from those who believe that while Boeing got a lot of things wrong, they were not the only party that contributed to the twin crashes of the 737 MAX. In the event, it seemed to simply remind us of what we already knew, or thought we knew.

I asked friends unconnected with aviation (who all watched it avidly) what new information they discovered. “Nothing new, Boeing was to blame, and the programme really nailed it…” was a general feeling. ‘Those guys (pilots and passengers) never stood a chance’, was the overwhelming view – an aircraft so badly designed that even well-trained pilots could not cope, including the Lionair pilots where the point was made that the captain “finished his training in the US” – this point seemed to hammer home the final nail. The emotive scenes of the wife of the captain and the passengers grieving are of course heart-rending, but do they detract from a documentary film that seeks the truth without drama and emotion? The grieving wife of the captain can be heard saying that he was well trained. Objectively, that is not something that she could know about. No doubt he was an avid student and performed as well as he could, given his training, but few pilots can perform beyond their training and as we see later, there are doubts about the training of pilots in general.

SEE: Flight Safety Detectives dissect the Netflix Downfall documentary

I have seen the Netflix documentary twice now and the second time I looked to see if there is another narrative that was omitted from the piece. The documentary never strayed far from what we know and can be proven – as one would expect, with legal people keeping an ever-watchful eye on these matters. It was spot on in nearly every point it made. But did it omit certain points which do not suit the story?

What concerned me, was that certain facts were omitted –some of which change the narrative a great deal. Today I will simply ask a few questions. Let us start with the most obvious omissions or were they obvious to everyone?

John Leahy

Perhaps the first one must be that Lionair was banned from operating in Europe until 2017 under the banned list published by EASA – the European Aviation Safety Agency. Was this mentioned? It was not.

The second omission was that Lionair, which was a small Indonesian start-up operator by international standards, placed the second largest order in aviation history in 2011 for over 200 737 MAX aircraft while still banned from flying in Europe. In 2013 they placed a similar order for a very large number of Airbus aircraft. Questions could therefore be asked about the judgement of the airline and the sales teams and the ‘due-diligence’ in such orders for sophisticated aircraft in such large numbers, but they were not raised during this movie.

What steps did Lionair take to suddenly jump from the aviation equivalent of being bottom of the 4th division of league football to the Premier League? That was not explained or even touched upon. There are no doubt good ways that an airline can turn itself around in the courtroom of regulatory and public opinion but it always entails a root and branch overhaul of culture and procedures. These steps, if taken, were not mentioned.

The chain of events that led to the first crash in October 2018 was more than two weeks long, involving serious errors in the engineering division of Lionair involving this aircraft being repeatedly dispatched with errors in the airspeed system until, the day before the crash, a vital part, the Angle of Attack (AoA) sensor, was replaced. This part, the provenance of which is still under discussion, and which was clearly faulty, should have then failed its post-installation test, and the aircraft grounded. Why Boeing was not asked to assist with such a serious fault in a new aircraft is never questioned. In any event, this was not carried out, leaving the pilots as the last line of defence. Now of course that is what they are there for! But to be that last line of defense when everything else has failed, they must be on top of their game and well trained to perform those duties.

Lion Air ordered 201 Boeing 737 MAX9 aircraft in 2012, making it the launch customer for the variant. (Boeing)

Identical scenarios

Let us go straight to the takeoff itself. The departure from that Indonesian airport was routine until liftoff when the stick shaker began to rattle the controls as it is designed to do when it detects a real (or in this case false) impending stall. The crew coped quite well with this first emergency, but as the flaps retracted, the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) system kicked in, a system which they knew nothing about, and which was repeatedly pushing the nose downward. It was beginning to overcome their efforts and was about to cause them to enter a deadly dive. At this point, the pilots discovered that there was a solution and carried out the existing Boeing Non-Normal

Procedure for RUNAWAY STABILISER which involved putting the STAB TRIM cut-out switches to CUT OFF – thus denying the stabiliser motor, the electrical power it needed to repeatedly lower the nose. Control was restored. The aircraft could then be trimmed manually as per the Boeing procedure and the flight continued to its destination some two hours later and landed safely.

Wait a moment! That’s not what happened in the documentary – they crashed. Surely? And in the movie, they did crash. Because the documentary did not mention once what happened the day before. This bears repeating – the day before.

The scenario just described was the same machine (the very same) taking off from Bali for Jakarta the previous day, but with a different crew, who experienced an identical, full-on MCAS event, just like the fatal one the next day, which killed all 189 souls on board. But the day before, 28 October, it was handled safely and did not crash. As a viewer, did you know that? Would you find it relevant?

Many people I have spoken with, did not know about this event, nor indeed did they initially believe it to be true until they searched reputable sources and found the story to be true.

Apart from the reputable aviation press, it is mentioned in the initial and final reports. Some people I speak to today, over two years later, regard this as complete fiction Given the two related events, resulting in a fatal crash the next day, one would expect them to be investigated alongside each other, since if one was safe, and the other fatal, we have a unique set of circumstances rarely encountered in aviation. A direct comparison can be made between a successful outcome and a fatal one. That opportunity rarely if ever presents itself yet if any investigation was conducted, it was out of view.

Much can surely be learned from two identical flights less than a day apart where one is safe, and one is deadly. Both had MCAS events, but with totally different outcomes. What then, was the difference? Why do we not know the names of the pilots on that first flight which landed safely, who were confronted with what has been oft described as an

impossible situation? Even US pilots, who one assumes are right up there when it comes to standards of training, stated afterwards that it was beyond anything they had ever experienced The two US Allied Union pilots used words in the documentary along the lines that the MCAS was beyond what a “normal” pilot could hope to handle. “Ten seconds was all he had… ten seconds….”

The unknown hero

This previous flight was widely reported at the time in the press but never gained any traction and searches for the data about “the one that got away” started fading quite soon after the event. Today in May 2022 I found it hard to find any reference to the pilots who saved their passengers from what the next day has been described as ‘certain death’. These pilot(s) saved nearly as many lives as Captain Sullenberger in ‘The Miracle on the Hudson’, using their combined training and systems knowledge, yet they are anonymous. That is quite extraordinary.

Bloomberg reported (an extract) as follows – “According to two people familiar with Indonesia’s investigation, that extra pilot, who was seated in the cockpit jump seat, correctly diagnosed the problem and saved the plane.” Sadly, the next day, a similar plane in the hands of a different crew faced an identical malfunction and crashed into the Java Sea killing all 189 aboard.

The jump seat pilot on the flight from Bali to Jakarta was from Lion Air’s full-service sister carrier, Batik Air and told the crew to cut power to the motor in the trim system that was driving the nose down. The crew next day was unaware of this action and can be heard checking their quick reference handbook, a summary of how to handle unusual or emergency situations, minutes before they crashed, as per flight cockpit recordings.

A few days after the fatal Lionair crash, we found out that the two Lionair pilots the day before (the one that did not crash) had a passenger in the jump seat – regular practice for pilots getting a ride home even from other airlines. The pilot in the jump seat was from Batik Air, a subsidiary of Lionair but crucially, he knew what was wrong and he dared to communicate his concerns to the operating crew. Once the STAB TRIM switches were set to CUT OFF as per the Non-Normal Procedure for a runaway stabiliser, the deadly part of the emergency was over. The aeroplane flew (not without difficulties) to Jakarta and landed safely, where it remained overnight with the dormant fault still present. That was of course an awful failure of the safety system. There are several reasons why the aircraft was allowed to take off again, but all opportunities to prevent that final takeoff were lost. Why did the documentary not address the failure to ground an aircraft which very nearly got the better of its crew?

I have travelled in the jump seat every week as a commuter for 30 years and I can tell you that I saw many things with many different carriers – not all of them pretty. But to intervene at a critical stage of flight you have to be certain of four things. That you know what is wrong, that the crew are not coping, that you are sure of how to fix it, and that you are going to die if you do not. Otherwise, you stay quiet – I can assure you. So to this pilot and the two at the controls who listened and then coped, many passengers owe their lives.

Some would not even be aware of what happened to them that day. The ‘unknown soldier; of aviation to whom so many owe so much, remains unknown except to very few who investigated the original crash.

Twelve full minutes of terror

The Boeing 737 MAX was announced in 2011 and first flew in January 2016. (Boeing)

What else was left out or not made clear? Did you get the impression that the whole incident happened very quickly? Most people I have asked think so, and say it was all over in a matter or a couple of minutes. The documentary in my view reinforced that erroneous perspective.

LISTEN to the Flight Satefy Detectives dissect the Lion Air accident

It didn’t happen in a couple of minutes. Lionair 610, the ill-fated aircraft flew from 23:20 GMT to 23:32 – 12 long minutes in all. Of those 12 minutes, about 60 per cent or more were spent struggling with the MCAS, which the day before was successfully overcome. That is like a lifetime on a flight deck – and this was a memory drill – one required to be known by heart as if your life depends on it because it does.

You will often hear of factors that are used to mitigate causes of crashes and pass the blame from ‘poor training’ to ‘human factors’. Startle Factor and Overload, along with Somatogravic Illusion are but three of these oft-quoted factors. And yes, these do exist and we can come back to those in a later piece. But right away let’s make it clear here that much of a pilot’s training is about, or should be about; handling high-stress situations and being able to drill down quickly into what matters.

For example, these pilots failed to completely carry out the ‘Memory Items’ of two critical checklists where it is accepted by manufacturers and operators alike that there is never time to look in manuals:

- The AIRSPEED UNRELIABLE checklist was required as they got airborne with the stick shaker going and various indications that made it abundantly clear that this checklist was needed. Failure to do so resulted in them not taking proper control of the flight path and leaving full power on until they crashed 12 minutes later. The aircraft hit the ground way beyond its designed maximum speed with full power applied.

- They failed to completely carry out the memory items for the RUNAWAY STABILISER, which to a well-trained pilot would have been obvious, as it was the day before to our jumpseat passenger/pilot. Instead, just before the final, fatal dive, the captain handed control to the inexperienced and (from the report) ‘below average’ co-pilot to ‘look in the manual’. For a ‘Memory Drill?’

Skill decline – a growing threat?

The emotive scenes of the wife of the captain and the passengers grieving are heart-rending, but do they detract from a documentary film that seeks the truth without drama and emotion?

Any suggestion that after several minutes, a trained pilot is still startled, or suffering from these other factors degrading his or her performance, when all those years of training should be kicking in, does not sit well with my experience of over 40 years in the training business in a major legacy airline and a low-cost carrier too.

In the 2021 February edition of Aerospace magazine and in AirlineRatings.com in April 2021, we wrote a piece covering what we called ‘Skill Decline and Skill Deficit’. In that piece, we discuss skill decline in detail. The gradual erosion of flying skills over time as training programmes are reduced in duration and quality, and automation dependency eats into the ability to fly manually. What became clear right after the second crash (Ethiopian in 2019) was that not only were pilots in some regions of the world not being trained well (and certainly not in handling the stabiliser on a 737) but that major US carriers had also started cutting back on training.

That is why I believe, that the US ALPA union pilots were saying soon after that “this was beyond our training.” Because that is true. But it should not have been that way at all. Generations of 707 and 737 pilots had been trained ad nauseam in the dangers of not understanding the vital and powerful effects of the stabiliser on a 737 if not managed correctly in several failure modes. Then sometime around 2005, it started to be reduced in importance in the training program and was eventually omitted or only touched upon in full flight simulator training. There are US pilots who have stated that they too would have not been able to cope and the documentary makes this point too. But were they not able to cope because MCAS was “unrecoverable” (which it clearly was in the right hands) or more likely, because it wasn’t covered adequately during their training?

Other issues? The programme makes much of MCAS not being trained in simulators. Even on the 737-800 NG (the previous model) training had all but ceased in many places on the existing Runaway Stabiliser procedure, never mind the new yet to be invented one. Even after the re-entry of the MAX recently, the ‘new revised training’ that is now given is still pretty much the same as it was 20 years ago, long before the Lionair and Ethiopian crashes.

It’s just that it wasn’t being taught as extensively. And even today you do not need a dedicated 737-MAX simulator to demonstrate an MCAS runaway, which looks very similar to any other runaway of the trim and is resolved the same way.

The fact that MCAS wasn’t in the manuals? It should have been of course but did it make any difference? Not one bit, since the average line pilot doesn’t possess an intimate knowledge of the systems that operate silently in the background. If you doubt this just ask any airline pilot you know well enough, to describe how anything ‘behind the scenes’ works on their aircraft especially if it is a Fly by Wire type! They will probably say they don’t know and don’t need to know. And that is true. In any event, both failures that occurred were Memory Items requiring no systems knowledge whatsoever. That is why they are called Memory Items. You perform them right away from memory with no reference to manuals.

Bandaging over the wound?

But these points are not the point of this piece. To finish this review of the Netflix documentary, it seems to leave everyone with an abiding sense of Boeing and the FAA as being responsible for everything that happened, that MCAS is now fixed and that we can all fly again with confidence knowing that the FAA has been reorganised and re-established its authority over regulating the manufacturers. The MAX is fixed and back flying almost everywhere and this awful double crash is so well understood that it can never happen again. Boeing has re-organised and has returned to its ethos of quality before profit.

Except for one thing. If there were, as early reports in the documentary point out, some elements of poor training of pilots in general, not only in certain regions of the world but even in the US and other places, then we have simply bandaged over a very large wound that is just waiting for the band-aid to snap.

Next time it won’t be MCAS because that has indeed been so well fixed that it would be unlikely to cause a similar event ever again. Pilots returning to the skies in the MAX are now given a training course with great focus on the operation of the stabiliser and its critical role in longitudinal stability on all 737 aircraft, and the MAX is no different. The same training course, incidentally, that all 737 pilots used to receive routinely. The current remedial training should always have been on the syllabus. There should never have been a need for ‘remedial’ training. However, this new training is mainly focused on MCAS recovery and associated systems.

There are many other systems on every aircraft that need just as much systems knowledge and training, but are they still being taught as a ‘tick item’ on a list of required items on a Type Rating course? Or like the Runaway Stabiliser Procedure – consigned to history because it takes too long to teach it. Or more damning, because it might make the 737 seem less easy to fly than other types which have more modern architecture and therefore are more automated? I hope not, but it is a question. Does Boeing now point this out to customers? I don’t know – as stated, this article is a series of questions that are begging for answers.

You can still turn a 737 upside down if the mood takes you – it’s a real manual aircraft in every respect and has very few FBW (Fly By Wire / AR architecture) built-in defences against poor flying skills, as seen on every aircraft designed in the last 30 years or so. Does every operator know that, or do they think a 737 is a Boeing version of the Airbus A320 series?

Are they told this when they buy them? It’s important to know, but does this make the 737 a bad aircraft? Not at all. The 737 was and remains one of the finest aircraft ever built, and will remain so for many years to come – perhaps 70 years from its first flight. You just can’t take shortcuts with the training of any airline pilot and especially not on an aeroplane which under all the fancy electronic wizardry is a very basic aircraft that can still fly with no computers working at all. You just have to know how to do it. Old-fashioned nonsense?

Many think so, which is why I have written this piece!

While we now train 737 pilots on every aspect of the MCAS system, do we fail to teach them on all types of aircraft about things like auto-throttle during Go Arounds, or the use of the Flight Directors during critical phases of flight? As recent major crashes and incidents have revealed, these fundamental skills also need to be taught. But are they considered by the Chief Financial Officer to be too time-consuming items on expensive type rating courses?

Are we spending enough time and money on excellent training? Or are we waiting and hoping that the automation cavalry will ride over the hill very soon? That is the nub of this piece.

Single pilot operations and the future

I started by saying I would simply ask questions to flush out further thoughts on the loss of two 737 MAX aircraft which should never have crashed. I finish on one more.

Can automation solve these problems, because many believe that this is the solution rather than the expensive alternative of more extensive training? With eMCOs (Extended Minimum Crew Operations) colloquially described as ‘removing one of the pilots’ firmly now ‘centre stage’ and the subject of extensive debate, that is a really big question.

We have seen above that even two pilots can sometimes struggle to solve multiple failure scenarios and one would not currently stand a chance. In the case of QF (QANTAS) 32, the A380 out of Singapore, it is well established that it took the combined efforts of all four pilots aboard to get that ultra-modern aircraft safely back on the ground. It will be an interesting debate for sure, and one we can return to here in future editions.

It is not about taking sides in this debate – this is much too important. What is needed is an honest assessment of the pros and cons of reducing crew numbers. The RAeS Flight Operations Group (of which I am a member, but not a spokesperson) is well placed to offer an unbiased and objective view, given the large number of very experienced members, who are to a certain extent no longer compromised by their former workplace codes of nondisclosure and company loyalty. They have no ‘skin in the game’ to speak and should be consulted and listened to most carefully.

John Leahy’s CV:

John Leahy started his extraordinary flying career in 1968 as a navigator and the pilot of British Airways (then BOAC) Boeing 707s. In 1980 he moved on to the Lockheed Tristar and then to a command on the Boeing 737 in 1984. John rapidly moved up the ranks being appointed Base Training Captain for the B737-200/300/400.

In 1990 he became the Senior Training Captain for the 737 from British Airways.

The next move was in 1995 when he was appointed Chief Technical Pilot B757/767/737 and responsible for the technical side of these three types concurrently and qualified to fly all three at the same time. He also wrote the Operations Manual for these three types and converted them into a modern A5 size for ease of use.

In 2000 John was appointed Chief Pilot on the B747-400 with 57 aircraft and 1000 pilots under his direction. John also devised new SOPs and re-wrote the Operations Manual for the 747-400.

John retired from British Airways in 2003 and in 2007 returned to the industry he loves as Flight Ops Auditor Ryanair (external).

In 2015 John was appointed Director of Safety at Ryanair and also joined the Board. He was responsible to the Board for the safety of the airline. John retired from that position in 2016.

During his career, John was also an air test examiner for all Boeing types for the British regulator the CAA. He also carried out air-test acceptance flights in Seattle on Boeing aircraft (737/757/767/747).