The setting: 12,000 feet over the choppy, menacing Pacific Ocean. A fictional, crippled TOPAC Airlines DC-4 descends, preparing for possible ditching. Aging girl-next-door Sally McKee turns to haunted nuclear scientist Donald Flaherty and blurts out, “I’m not going to run away anymore.”

“What are you hiding from?” he shoots back.

“Myself,” snaps Sally (she’s flying from Honolulu to San Francisco to consummate a pen-pal romance). “He’s a clean, wonderful man,” she continues. “He has a right to know what kind of person I am. I’m going to tell him,” she says, furiously rubbing off layers of facial make-up. “I’m not wonderful, not clean, not kind. Telling you these things is easy. You’re a stranger and I’ll never see you again.”

The film, of course, is The High and The Mighty, the airline movie against which all others are measured. While John Wayne battles fate and edges his aircraft on to a safe landing, the real action is back in the cabin.

Ah, there’s the essence of it: conversational confession on high, with few, if any, consequences. Although figures are elusive to non-existent, it’s anecdotally amazing how many people open up on airplanes, baring their souls to seatmates they’ll probably never see again. Driving the exchanges are passionate issues and pure proximity believes Marc Berman, a million-mile frequent flyer and licensed psychotherapist from the Boston area. “You’re strangers on an airplane,” he says. “I think it’s the anonymity of it…being in the same place, the same space.” Then there’s the absence of consequence. You’re able to vent emotion, to connect with someone “and know there are not going to be any ties going forward.”

For some flyers, airliners are the perfect incubator for verbal intimacy between perfect strangers. Berman labels it a “protected environment.”

Emotional triggers

Emotion is often at the epicenter of such exchanges. Flying back from the West Coast to Hawaii after the death of her father, Jeanne, a long-time friend and colleague of mine, was sandpaper-sensitive, emotionally wrung out. So was her seatmate.

The conversation, as virtually all do, started off casually enough. Jeanne remembers it began “with the usual question.” Her seatmate asked why she was going to Hawaii. Jeanne told her she was returning home after the death of her father on the Mainland. That really broke the ice. Out tumbled the reason her seatmate was headed for Hawaii. “Her husband (in the military) had attempted suicide and was in intensive care…For the next four hours, I learned her life story” remembers Jeanne.

A father was dead; a husband’s life hung in the balance. Each woman took the other into her confidence, “dealing with death in the same odd fashion.”

Unlike most such encounters, these two temporary seatmates kept in touch. When Jeanne e-mailed her to ask how things were going she wrote back that her husband had died. Jeanne agrees with the premise that the reason people talk to strangers on airplanes is, “They don’t think they will ever see the stranger ever again,” that nothing will come of the personally intimate conversation. Yet this time it did. And that’s unusual.

Also unusual is exchanging names. Berman says it’s part of the code entailed in anonymous interaction. In this case, Jeanne – an innately compassionate person – broke both taboos.

It’s amazing how many people face common challenges. The wife of a writing colleague of mine was on a flight to Los Angeles. Her seatmate was a candy company executive. They struck up a conversation about children. My colleague’s son was in his teens, beset by a learning disability and the disciplinary problems that can go along with it. By chance, her seatmate’s son had the same problem. “The discussion centered on how to deal with the situation,” remembers my friend. The seatmate’s advice was not to try to exert iron-willed control over her kid, that the goal is to give guidance, “to keep them in the race until they figure it out themselves.”

“So,” says my friend, “that’s what we did.”

It worked. The young man did figure it out himself. Today, “He makes a hell of a lot more money that I do,” smiles my colleague.

Conversations leading to action perhaps aren’t as common as those which follow the “clean break principle.” As colleague Lisa Davis, a Chicago-based travel journalist says, people feel free “to discuss all their personal drama…because their seatmate has no influence on their lives. If you tell a friend, then there’s accountability. You have to answer to someone.”

Timing

Ever notice how the chatter seems to pick up not too long before landing. Conversation can end up three ways: somebody puts their headphones on and politely turns away. They engage into soul-searching dialogue. Or, they exchange surface pleasantries and go about their own lives. It’s the latter – not dismissive, not intimate – that’s most common aloft.

Berman believes the reason for that “is their no strings attached…no obligation to feel you have to continue to talk with somebody. Because the flight is over.” He says such a strategy avoids the deep-probe interchanges “where you feel, ‘Uh oh. If I open up a can of worms here I’m going to have to manage it.’”

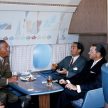

Location – the first class divide

Fate and timing factor into who talks and who doesn’t. So does where you sit. There’s not a lot of conversation up front, in the pointy end of the airplane. First class “is generally a very, very quiet place,” says David Marcontell, a high-mile aerospace executive. It’s one of those intuitively understood things. “It’s not because [business travelers] are not friendly,” he says. It’s because they’re there to work, unwind or relax. It’s their time; their space. The last thing they want is an intimate interchange.

A globetrotting U.K. resident accedes he’s, “not very sociable.” When hurtling through the heavens, if a seatmate persists in trying to fire up a conversation he immediately starts talking about his job: compiling and analyzing statistics. “That normally stops them very quickly.”

While coach may not be a veritable conversation pit, a lot more talk goes on in the back. “It’s a very different place,” says Marcontell. Behind the curtain, the aft of the airplane is a land inhabited by folks who often don’t fly as much. Marcontell says, “They are far more willing to talk about their sports teams, their families.” They’re excited about flying, in good spirits and want to share the experience. He contends such elbow-rubbing (literally), we’re-all-in-this-together ambience can “spawn some interesting conversations.”

Unexpected encounters – welcome and otherwise

Books are a way to break the monotony aloft, while keeping psychic intruders at bay. Business traveler and friend Marian Boyd was on a flight from Dallas/Fort Worth to New York JFK and looking forward to reading a mystery novel. A couple of times the guy sitting next to her made a comment or two, but Boyd smiled politely and succinctly and continued to read. “He took the hint and started reading his book.”

As the flight approached JFK, the pilot put the aircraft into a holding pattern. That’s when Boyd noticed the book her seatmate was reading was in another language. She asked the man if it was a good read. The question broke the ice, leading to “one of the most interesting conversations I’d ever had,” remembers Boyd. The man sitting next to her was Astronaut Tom Stafford. He was on his way to the then Soviet Union for the Apollo-Soyuz space mission. “I was kicking myself,” for not having taken up his verbal invitation to speak earlier. For the next 45 minutes before the flight landed the Apollo astronaut “patiently and thoroughly answered every imaginable question I could possibly ask.”

An in-flight encounter of a decidedly different kind befell Kathy, my wife and then-fiancé. On a flight from Atlanta to Dallas Love Field the guy in the seat next to her clumsily tried to strike up a conversation by asking, “Hey babe, what’s your sign (these were the late sixties folks). The one-sided conversation cascaded down hill from there, all two-and-a-half hours of the flight. Near the end of the trip he suggested they get together later for some “tea” – the decidedly illegal variety.

The awkward silence was followed by another question. “What do you do?” he asked. Having just gotten a fellowship to study criminal justice Kathy responded to the guy by stretching the truth a tad. “I’m a narc (narcotics officer)” she shot back.

The silence for the rest of the trip was deafening.

Some passengers deliberately turn a deaf ear to those next to them. Others open up and let their souls be seen. Most merely exchange passing pleasantries. Either way, “people share some common social currency when they’re aloft,” says Marc Berman.

The value of that currency can be as cheap, or precious, as you want. Just how you choose to redeem it is up to you.