The man who led the development of the aircraft that amazed a generation and opened up travel for ordinary people has died at the age of 95.

Legendary Boeing engineer Joe Sutter led the team behind the company’s iconic Boeing 747, known affectionately as the “jumbo jet’’ and was responsible for pushing the boundaries of 1960s aerospace technology.

A native of Boeing’s birthplace, the US city of Seattle, and the son of a Slovenian immigrant, Sutter was born in 1921 and grew up on a hilltop overlooking the manufacturer’s plant.

“My friends all wanted to fly airplanes but I set my heart on designing them,’’ Sutter said in his book “747’’. “The futuristic flying machines I sketched as a boy would carry passengers in safety and comfort to the far continents, conquering oceans in a single flight. Little did I know I would grow up to realize these dreams.’’

Sutter was a graduate of the University of Washington and started at the Boeing plant after serving in the US in Navy World War II and was courted by both Boeing and the Douglas Aircraft Company after the end of the war.

He initially accepted the higher Douglas offer but took what he thought was a short-term job with Boeing while his wife delivered the couple’s first child.

That job with Boeing’s small aerodynamic group working on the piston-powered Stratocruiser would be the start of a long and illustrious career that would see him work on many of the airline’s early jets.

“He personified the ingenuity and passion for excellence that made Boeing airplanes synonymous with quality the world over,’’ Boeing Commercial Airplanes President Ray Conner said in a tribute sent to staff.

“Early in Joe’s career, he had a hand in many iconic commercial airplane projects, including the Dash 80, its cousin the 707 and the 737. But it was the 747 – the world’s first jumbo jet – that secured his place in history.

Joe led the engineering team that developed the 747 in the mid-1960s, opening up affordable international travel and helping connect the world.

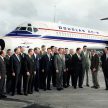

“His team, along with thousands of other Boeing employees involved in the project, became known as the Incredibles for producing what was then the world’s largest airplane in record time – 29 months from conception to rollout.

It remains a staggering achievement and a testament to Joe’s “incredible” determination.”

Sutter remained active with Boeing long after his retirement and continued to serve as a consultant as well as an ambassador for the company.

“By then his hair was white and he moved a little slower, but he always had a twinkle in his eye, a sharp mind and an unwavering devotion to aerospace innovation and The Boeing Company,’’ Conner said.

Fittingly, he was on hand to celebrate our centennial at the Founders Day weekend. He was one of a kind.

“Joe was loved. He made a difference in the world. He made a difference to us. We will miss him and cherish our time with him.‘’ The 747, in fact, was not supposed to carry passengers for many years.

At the time the world was looking to supersonic travel with the Boeing SST and the Concorde as the future in aviation. But Boeing has sold well over 1500 of its 747s and the aircraft is still in production, with a new model still wowing passengers.

Giving life to the plane that changed the world was a challenge that brought Boeing, the world’s biggest aerospace company, the then-biggest engine maker Pratt and Whitney and the legendary Pan Am to their knees.

First flight of the latest model of the 747 the -8 Intercontinental

In the late 1960s, Boeing’s resources were stretched to the limit as its engineers grappled with the complexities of its US government-sponsored supersonic transport, dubbed the Boeing 2707, which was eventually scrapped by Congress on May 20, 1971, despite commitments for 115 from 25 airlines.

The 2707 was to carry three times the number of passengers as Concorde at twice the speed.

At the time, the 747 was considered only an interim solution that might carry passengers for five to 10 years until the supersonic transports took over.

Fortunately, Boeing had appointed Sutter to the project and he was to father the classic jet.

Sutter was always was modest about his role. “I was the only qualified person available,” he said in a 2009 interview with AirlineRatings. “All the smart guys — Maynard Pennell, Bill Cook, Bob Withington and many others — were tied up on the SST while Jack Steiner was heading the 737 program.”

The 747 was from the outset designed to be converted to a freighter as the superseded model was relegated to cargo routes. “That’s what Boeing’s marketing people thought,” Sutter said. “They estimated we’d probably sell 50 or so for passenger use.”

The 747 was a mass-travel dream of Pan American World Airways founder Juan Trippe and Boeing chief Bill Allen. Trippe had started mass travel in 1948 when he introduced economy class onto 50-seat DC-4s.

But the 747 was much bigger and could carry more than 350 people — almost double the 707 — and allow the carrier to slash fares.

It is impossible to find anyone who recalls whether there was a definitive business plan for the 747. But traffic was booming for the airline industry, which had enjoyed the growth of 15 percent a year through the early 1960s as passengers flocked to jets from piston-engined planes.

Trippe was a man on a mission. He wanted to make travel affordable and he believed the 747, with the high bypass turbofan engines developed for military transports, could do just that. The 747 was expected to cut operating costs by 30 percent over the 707 model.

Pan Am loved the concept but most airlines were terrified of the jumbo’s size. Regardless of the reticence of other airlines, on April 13, 1966, Pan Am ordered 25 747s at $22 million apiece. Today, they cost well over $350 million.

But the trickle of 747 orders was not the major problem. It was the weight. The jumbo was initially supposed to weigh 250,000kg at take-off but by the time it took its first flight design changes impacting range, altitude, speed and fuel burn saw it top 322,000kgs.

According to some insiders, the company threatened to cancel the 747 program unless the engine maker agreed to additional thrust to solve the problems.

A solution, to run the engines at higher temperatures to give more thrust, was found and within six months of entering service, the jumbo was performing at acceptable levels.

But it came at a price and Boeing was mired in debt from the 747 program, owing banks $1.2 billion, $7.2 billion in today’s money. Despite the many problems in its manufacture, the birth of the 747 was an amazing feat.

With the extra space on the 747s, airlines splashed out with upper- deck lounges and many also had lounges at the back of economy. Sadly, a Boeing plan for a lower- deck lounge, called the Tiger Lounge because of the fabric design, never made it.

The spacious age, however, was short-lived, with airlines responding to a demand for cheaper travel by adding more seats. In economy, that meant additional seats across the plane’s width.

Today, the 747 is still the “Queen of the Skies” to many and for billions of passengers it is the plane that allowed them to see the world