The stunning profit results at Air New Zealand, Qantas and at US airlines have prompted many media and commentators to talk about lowering airfares, while some consumer groups have claimed that airlines are too greedy.

These types of comments show a lack of understanding of what drives sustained and long term fare reduction in the airline industry – technology.

Stunning advances in engine and computer technology are the two main reasons that airfares have stayed much the same as they have been for the past 50 years, while average weekly earnings have soared.

At the beginning of the jet era the cost of a return flight to London from Australia or New Zealand was around a year’s salary now it’s just over a week’s wages.

Unless airlines are making money they cannot invest in new aircraft that in some case burn up to 25 per cent less fuel than the ones they will replace.

But the savings don’t end there.

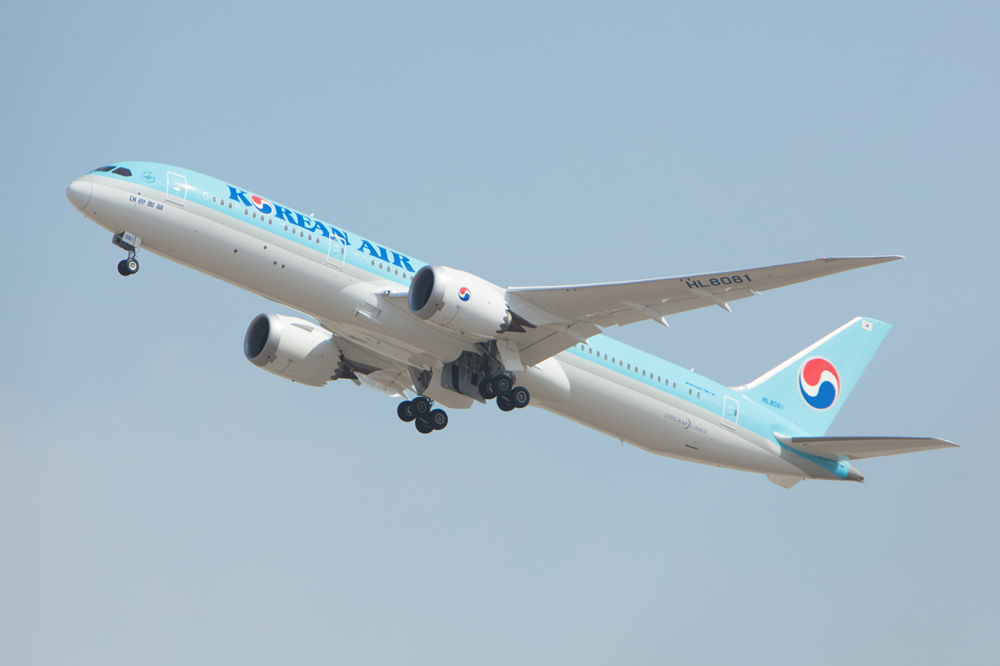

The maintenance on a Boeing 787 or Airbus A350 for instance is half that of the aircraft it replaces (Boeing 767) – and that is a huge saving in parts and labour.

Comparisons between the first jet engines that powered the 707 and DC-8 and today’s GE90 engine on the Boeing 777 are extraordinary.

The first jet engines needed to be overhauled every 500 hours – today some engines stay on the wing for 30,000 hours. And the cost of scheduled replacement parts on the early jets would equal the cost of the engine within eight years of purchase – now that is 30 years.

All of those savings are before you consider the fuel savings with a reduction of about 70 per cent in fuel per passenger consumed over in 60 years.

Incredibly impressive numbers but they cost billions in investment to bring to market.

To design, build, test and deliver a new aircraft costs between US$10 to US$15 billion and that is before the first one is handed over. And an aircraft manufacturer must sell about 300 to 400 to breakeven and a number of recent aircraft programs have had much higher breakeven figures.

Computer technology has revolutionize the aircraft themselves and the back end of the airline industry – the part passengers never see, although today passengers interact with it every day with online reservations.

Consider just one example the humble airline ticket. It used to be hand written with five carbon copies that would go off to various departments for processing. Now it is a barcode on your mobile. The savings are staggering.

Industry wide profitability is a major concern with airlines, since de-regulation was introduced in the US in 1979, struggling to make between 1 and 2 per cent net profit in a good year.

De-regulation enable virtually anyone to start an airline and fly wherever they liked within the United States. The result? The airline industry in the US has been devasated.

Over 200 airline have gone bankrupt or been forced to merge since de-regulation was introduced into the US. According to the Airlines for America (A4A) association the profit margin for US airlines between 1955 and 1977 averaged a modest 2.8 per cent. However in the first 10 years after deregulation it slumped to just 0.4 per cent and between 1990 and 1994 it dropped further to a negative 3.3 per cent before bouncing back between 1995 and 2000 to 3.8 per cent.

However from 2001 to 2009 to slumped to -6.30 per cent with total losses of $65.1 billion. From 2010 to 2014 airline profitability has bounced back after a series of mergers and the easing of fuel prices to a profit margin of 2.9 per cent.

Certainly fares have risen since 2000 but nothing like the increases of CPI and average weekly earnings. While increases vary from country to country an interesting comparison comes from the United States – the world largest airline market.

Since 2000 air fares with ancillary charges have risen by 26 per cent but the CPI has jumped 37.5 per cent.

But that comparison pales when you look at motor fuel which in the US has jumped 123.2 per cent up to 2014, while jet fuel leapt a massive 254.5 per cent in the same period, although both have tumbled in the past nine months. A pass to the world’s number theme park Disney World has soared 115.2 per cent and disposable personal income has climbed 54.4 per cent.

A major point of contention with some consumer groups particularly in the US is the recent (and unusual) airline profitability combined with the practice of over-booking flights and charging for baggage and other ancillary services.

The problem is the high load factor required to make a profit.

According to A4A data the breakeven for US airlines is a load factor of 83.4 per cent. This is far higher than it was in the 1970s (56.7 per cent) and the 1990s (66.20 per cent) and reflects the declining fares relative to other costs. The same figures apply generally across the globe.

Thus overbooking has become more important because of the simple fact that no-show rates can be as high as 10 per cent. However more sophisticated computer modelling had enabled airlines to better predict no-show rates and thus airlines have reduced overbooking rates from around 12 per cent 10 years ago to just 5 per cent today.

The rise in ancillary revenue is annoying to many but airlines have simply responded to new marketing ploys as passengers are attracted to the lowest fares. This type of base fare plus options was started by low costs airlines and many traditional airlines have been forced to follow “to compete on price.” This is particularly the case in the US but less so elsewhere.

Air New Zealand has worked this concept very well with its pricing of domestic and Trans-Tasman fares with four simple to follow tiers; Seat, Seat+Bag, The Work and Works Deluxe. Intending passengers can see at a glance the fare on the opening page and what it provides. One of the criticisms of the base fare plus options is that with many airlines the “full fare” is not revealed until the passengers is well into the booking process.

The charging for checked baggage in the US as led to many passengers taking more carry-on with them into the cabin which results in very congested overhead bins and slow boarding and deplaning times.

And here is the twist in this profitability debate.

Several years ago Boeing was considering a replacement for its 180-200 seat single aisle Boeing 737 that would have been an all new aircraft with two aisles with a configuration in economy of 2-2-2. It would have been the ultimate comfort aircraft with almost twice the overhead bin space and with only aisle and window seats. Problem was that with a chronic lack of profitability at the time airlines turned it down for a more modest engine upgrade.

A similar concept from McDonnell Douglas in the 1980s was abandoned because airlines were not making money.

So passengers will not get the quantum leap in comfort nor will they get the lower fares that such an aircraft would have brought to the market. So nobody wins – particularly the passenger.

Even on current model aircraft some US airlines don’t rate well when it comes to fleet age with Delta’s fleet age average at 17.2 years compared to Air New Zealand at just 7.9 years. However with profits returning Delta is now aggressively investing in new aircraft.

The debate about airline profitability needs to be far better balanced with the long term viability of the industry as the cornerstone for only a prosperous industry can deliver genuine long term and sustained reductions in airfares.