Thunderstorms: a must to avoid

13 January, 2015

7 min read

By joining our newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy

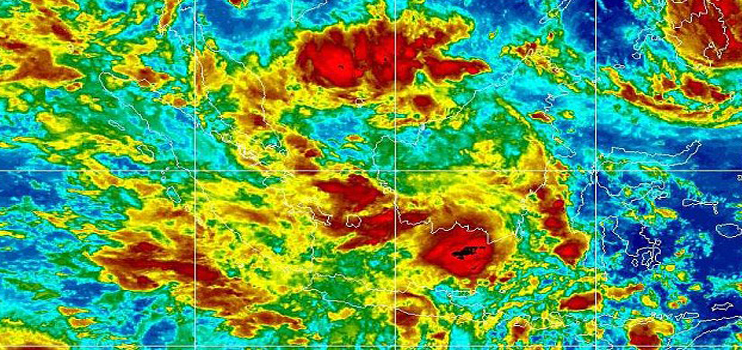

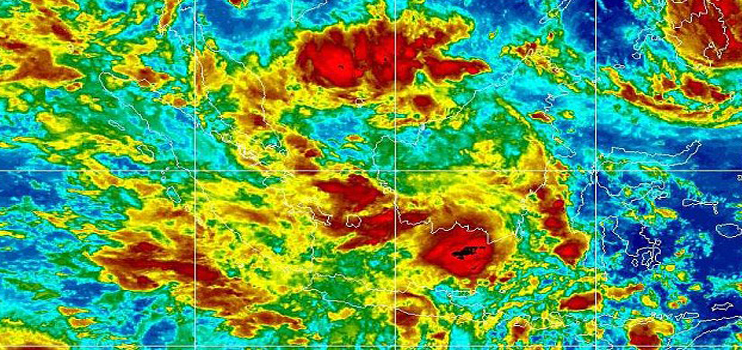

Talk to professional pilots and aircraft accident investigators and here’s what they’ll tell you about thunderstorms: avoid them. Don’t try to outclimb them in an attempt to overfly bad weather. Don’t attempt to ‘shoot the gap’ between thunderstorm cells. Give convective, tempestuous thunderstorms wide, wide berth. Respect the fact that they can ruin your day.

AirlineRatings.com took a look at some of the more notable thunderstorm–related crashes. We excluded wind shear accidents that occurred close to the ground, on takeoff and landing, focusing on encounters during climb or at cruise altitude. Despite the fact specific Probable Causes may differ, a common thread runs through the record: pilots should never come perilously close to, or actually penetrate, thunderstorm cells.

Suggested Read: Freak thunderstorms set to rise

The record:

Air France 447

It’s tempting to place the June 1, 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447 in this category. But we won’t. Even though the A330’s route over the mid-Atlantic, off the coast of Brazil, put its flight path near a broad band of thunderstorms, the French air accident investigatory agency, the BEA, said the crash was not due weather, but a deep aerodynamic stall. All 228 on board died on the Rio de Janeiro to Paris flight.

The accident remains one of the most controversial in history. But it doesn’t exactly fit the classic mold of thunderstorm encounters. Others do.

Southern Airways 242

The DC-9, on a short hop from Huntsville, Alabama to Atlanta, attempted to shoot the gap ‘twixt two thunderstorm cells April 4, 1977. Approaching a line of storms at 17,000 feet the pilot looks down at his black & white Bendix X-band radar. “Looks heavy,” he says. Nothing’s going through that.” Then, something catches his eye. “See that?” he asks the first officer (co-pilot). “

That’s a hole isn’t it?” responds the first officer.

“It’s not showing a hole, see it?”

Shortly thereafter the first officer asks the captain, “Which way do we go across, or go out? I don’t know how we get through there.”

The pilot responds, “I know you’re just going to have to go out and [do it].”

“Yeah, right across that band,” answers the first officer.

A pair of thunderstorm cells flank the gap that Southern 242 attempts to squeeze through. The one to the north tops out at 46,000 feet; the one to the south forms an anvil-like plateau 5,000 feet higher.

As the first officer, who was doing the actual flying, banks to the left he says, “All right, here we go.” In an instant Flight 242 enters a liquid hell with baseball-sized hail crashing against the fuselage.

Both Pratt & Whitney JT8-Ds literally suffocate. The compressor blades of the powerplants stall, killing the engines. The DC-9 is suddenly a glider.

The crew makes an heroic, but futile, attempt to land on a small rural road. It fails. 72 die, including nine on the ground. Twenty-two originally survive.

In its Probable Cause finding the United States National Transportation Safety Board said the crash resulted from “the total and unique loss of thrust from both engines while the aircraft was penetrating an area of severe thunderstorms.” A dissenting NTSB member said the accident was caused by “the captain’s decision to penetrate rather than avoid an are of severe weather.” The dissenting member also blamed the crash on “the reliance upon airborne weather radar for penetration rather than avoidance of the storm system.”

Braniff International Airways 352

If one captain decided to penetrate a thunderstorm system, nine years earlier another opted, too late as it tuned out, to do a 180-degree turn and try to escape.

Flight 352, a four-engine Electra propjet, is making the short hop from Houston to Dallas May 3, 1968, prime thunderstorm season in Texas. While at 20,000 feet the crew asks Air Traffic Control for permission to descend to 15,000 feet and deviate to the west. ATC responds by saying other flights are avoiding the weather by circumnavigating it to the east. The crew responds, “On our [radar] scope here it looks like…a little bit to the west would do us real fine.” Controllers okay a descent to 14,000 feet. Then Flight 352 asks ATC for permission to descend to 5,000 feet, and inquires if there is any hail in the area. Air Traffic Control answers, “No, you’re the closest one that’s ever come close to it yet...I haven’t been able…well I haven’t tried to get anybody to go through it, they’ve all deviated around to the east.”

Minutes later Braniff 352 runs into that hail and requests a 180-degree turn. ATC okays the exit. The Electra never makes it out, breaking up in mid-air. 85 dead.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board’s Probable Cause finding?: “The stressing of the aircraft structure beyond its ultimate strength during an attempted recovery from an unusual attitude induced by turbulence associated with a thunderstorm. The operation in the turbulence resulted from a decision to penetrate an area of known weather.”

In the wake of 352, NTSB recommended airlines emphasize weather radar be used to avoid, not penetrate, thunderstorms.

It’s a refrain that still rings true today.

Northwest Airlines Flight 705

Thunderstorms aren’t unusual over the Everglades of the U.S. state of Florida, even in February. On climbout from Miami International en route to Chicago on February 12, 1963, Northwest Flight 705, a Boeing 720, requests Air traffic controllers allow it to climb to a higher altitude to avoid storms in the area. 705’s crew then tells ATC, “We’re in the clear now. We can see it out ahead…Looks pretty bad.”

Controllers clear 705 to climb. ATC and the crew talked about moderate to heavy turbulence. Then, Flight 705 radios controllers, “You better run the rest of [the departing flights] off the other way.”

The 720 climbs fast and furious, as much as 9,000 feet per minute. Then, it starts to fall. Somewhere below 10,000 feet the aircraft comes apart. 43 people perish.

Investigators found the Probable Cause of the crash to be up and downdrafts, the kind associated with thunderstorms. Those gyrations led to the in-flight breakup of the 720.

While thunderstorms per se usually can’t pull an airplane apart, “turbulence [associated with the storms can] cause an aircraft to exceed its structural limits and literally rip of the wings,” said retired Major General Timothy Peppe, Chief of Safety and Commander of the United States Air Force Safety Center in a presentation for the U.S. National Weather Association. This is what happened to Northwest Flight 705.

That’s why the experts continue to counsel avoidance. Not penetration, not attempts to overfly or slip between cells.

New tools for safer flights

In an effort to equip pilots with the latest tools to meet the thunderstorm avoidance challenge the U.S. avionics company Rockwell Collins unveiled its new MultiScan ThreatTrack™ weather radar in 2014.

Contending it “provides unprecedented atmospheric threat assessment capabilities for transport aircraft,” the system goes beyond predicting hail and lightening within a thunderstorm cell. It actually alerts pilots about treats “adjacent to the cell.” Should the cells be growing ahead and below the aircraft, ThreatTrack Predictive Overflight™ protection alerts pilots if the cells will be in their airplane’s flight path.

Then there’s turbulence detection. The system breaks turbulence into two categories: severe and “ride-quality.”

When’s the system coming to a carrier you? American Airlines is debuting the new radar on its Next-Generation Boeing 737 fleet. A number of other carriers have opted for the new device for some of their aircraft. Among them are AirAsia, Silk Air, China Eastern, EVA Air, VivaAerobus, Air Algerie and Lion Air.

The new radar holds the promise of “helping pilots better navigate disruptive weather threats,” as wells a “smoother flights,” contends Steve Timm, Rockwell Collins vice president and general manager for Air Transport Systems.

New detection gear is great, as long as pilots use it to absolutely avoid thunderstorms, not penetrate or skirt them too closely. Good detection tools are never a substitute for good decision-making. If there’s one lesson the accident record teaches unambiguously it’s that.

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

No spam, no hassle, no fuss, just airline news direct to you.

By joining our newsletter, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Find us on social media

Comments

No comments yet, be the first to write one.